Saudi Arabia's economic crisis, explained in 10 graphics

|

But the the dual shocks of coronavirus and tumbling energy prices have hurt its plans, particularly in the non-oil sector, which is forecast to contract by 14 percent this year.

For your average citizen in Saudi Arabia, that means only one thing - more belt tightening. These are the key threats.

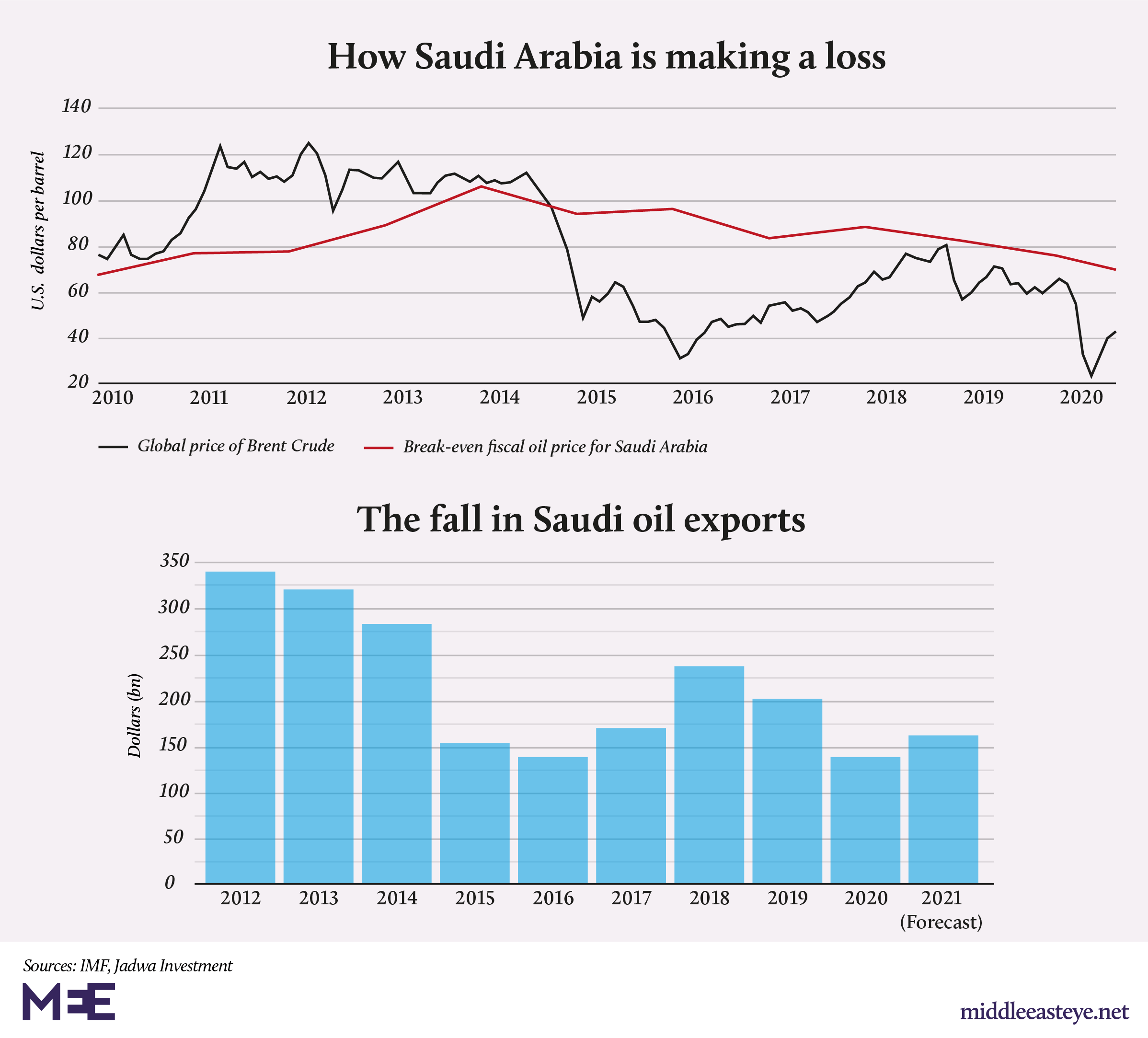

1. Saudi Arabia can no longer rely on oil

Oil revenues account for around two-thirds of the kingdom’s exports. But while Saudi Arabia was once responsible for nearly 30 percent of global oil exports, that figure has now dropped to just 12 percent, according to Capital Economics.

Riyadh started a price war in March in an apparent bid to damage rival producers, even as global demand was sinking due to Covid-19. It flooded the market, but in doing so saw its crude export revenues dropped by 65 percent compared to April 2019. “The sharp decline in oil prices, exacerbated by demand loss from the pandemic, has hit Saudi Arabia particularly hard,” said Boris Ivanov, founder and managing director of consultancy GPB Global Resources.

|

Nor is the global outlook positive: demand is projected to fall “by 8.1 million barrels a day, the largest in history” because of Covid, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). Looking forward, the organisation predicts that demand will peak by 2030 due to the rise in renewable energy.

2. Tourism won't come to kingdom's rescue

Saudi Arabia had hoped that tourism would be a key part of Vision 2030, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s diversification project, with a target of 100 million visitors a year by the end of the decade.

In the wake of Covid-19, Riyadh is now predicting a 35-45 percent decline in tourism - equivalent to a drop in revenues of $28bn in 2020. Those numbers seem optimistic, given the global industry is predicting a fall of 58-78 percent this year.

“Any country depending on tourism is reassessing things in light of the pandemic,” said Bessma Momani, interim assistant vice-president, international relations, at the University of Waterloo.

Another setback is the decision to limit the annual Hajj to 1,000 domestic pilgrims. Umrah pilgrimages have been halted since March. “Hajj is a big money maker, and the lost revenue is needed," said Theodore Karasik, a senior advisor to Gulf State Analytics. “Losing it for two years in a row will hurt.”

|

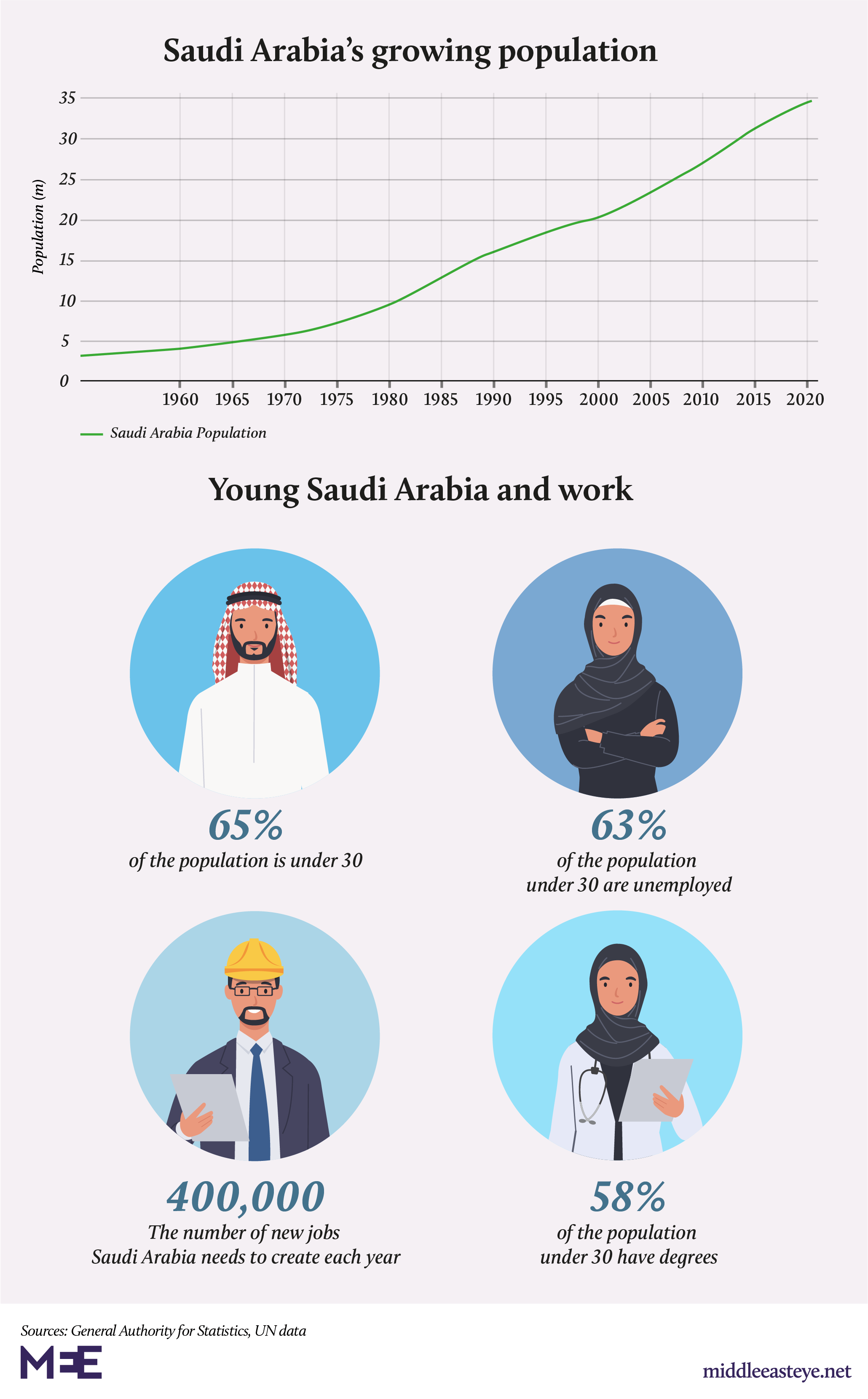

3. Saudi millennials: Educated and unemployed

The kingdom’s population has been grown fast for decades, doubling since 1990. But for Saudis born during the past 30 years, jobs are in short supply.

Almost two-thirds of the population are under 30 - and most of them are unemployed university graduates.

A process of “Saudization” will see an estimated 1.2m foreign workers leave the kingdom by the end of 2020, opening up opportunities for locals – but only if businesses can survive the pandemic and its economic consequences, and are prepared to pay higher wages.

|

“Saudis are far more expensive than expats,” said Rory Fyfe, managing director of MENA Advisors, “so if firms are cutting expats due to cost considerations they aren’t going to be replaced with Saudis.”

Momani said: “This is going to be a real reckoning for the labour market. We have already seen trends of nationalisation in the labour force, and Covid will accelerate this.”

4. Saudi Arabia citizens: Less income, more tax

Low- to no-taxes were once a mainstay of Saudi life, only increasing in recent years as falling oil prices prompted the government to seek new ways to generate income.

When Riyadh first introduced VAT and reduced fuel subsidies in 2018, it dampened the economic hit by introducing a cost of living allowance for about one million public employees, budgeted at 1,000 Riyals ($267) a month.

|

But in July, as part of austerity measures, that allowance was scrapped, saving the kingdom some $4.8 billion a year. Then VAT trebled to 15 percent. “The two will certainly have an impact on spending and hurt the economy,” said Fyfe.

One indication of Saudi Arabia’s declining standard of living are falling vehicle sales, which having skidded off a cliff since the last big oil price drop in 2015, when there were 800,000 car sales that year, to 400,000 in 2018. Vehicle sales are now forecast to drop by a third again in 2020 because of the latest VAT hike.

Higher prices are particularly felt by poorer citizens, with some 2.4m receiving financial assistance, according to a UN Special Rapporteur report on extreme poverty in the kingdom, released in 2017.

Saudi Arabia’s GDP per capita is relatively high on a global level, at $21,767. But this figure masks inequalities within the kingdom, and is significantly lower than other Gulf states, including UAE ($43,103) and Qatar ($64,782).

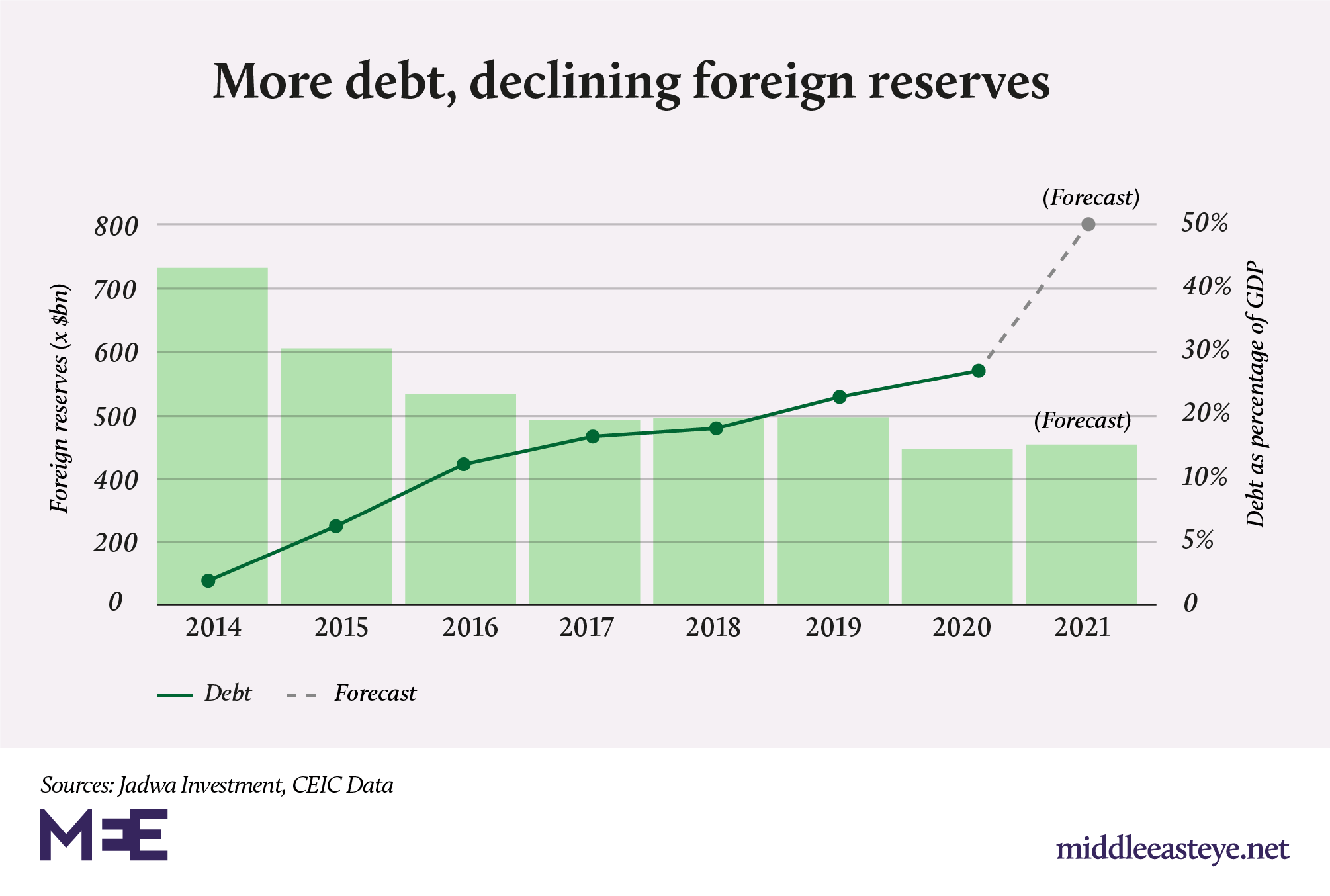

5. Saudi Arabia's debt is growing

As the world’s largest oil producer, Saudi Arabia traditionally has had no need to borrow money, so long as government spending and royal largesse did not outpace revenues.

But in 2015 falling oil prices forced the kingdom to turn to the international markets. That debt has increased as oil prices have remained low. Trillions of dollars are also needed to fund Vision 2030 projects.

|

| Add caption |

This year, lower oil prices and Covid-19 prompted Saudi Arabia to borrow $26.6bn after it burned through foreign reserves and announced a stimulus package of $32bn.

The kingdom’s debt could rise further after the government raised its debt ceiling from 30 percent to 50 percent from 2022. As such, Saudi Arabia will now have to act like a more regular national economy in how it spends as well as raises money, such as through increasing taxes.

One looming danger for the kingdom is that if debt keeps rising and foreign reserves are further depleted, then the riyal’s peg to the dollar will come under pressure.

6. Delayed: The Kingdom Tower

If there is one symbol of Saudi Arabia’s economic challenges then it is the unfinished $20bn Kingdom Tower, also known as the Jeddah Tower.

A project of Saudi tycoon Prince Alwaleed bin Talal’s Kingdom Holdings, the planned 1,000m-high landmark is intended to top Dubai’s Burj Khalifa, the world’s current tallest tower.

|

Construction began in 2013 and was supposed to be completed by 2020. But only a quarter of the tower has so far been built.

Work ground to a halt in early 2018, around the same time that bin Talal was released from three months detention in Riyadh’s Ritz-Carlton Hotel, after being rounded up with dozens of other influential Saudis in a wave of arrests ordered by Mohammed bin Salman.

“There were rumours that work was going to restart in the first quarter [of 2020], but the coronavirus pandemic may have prevented that,” said Fyfe.

“One would think the Saudis would find it embarrassing to have a huge uncompleted building looming over Jeddah. Maybe it will be rescoped smaller and finished off eventually.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.