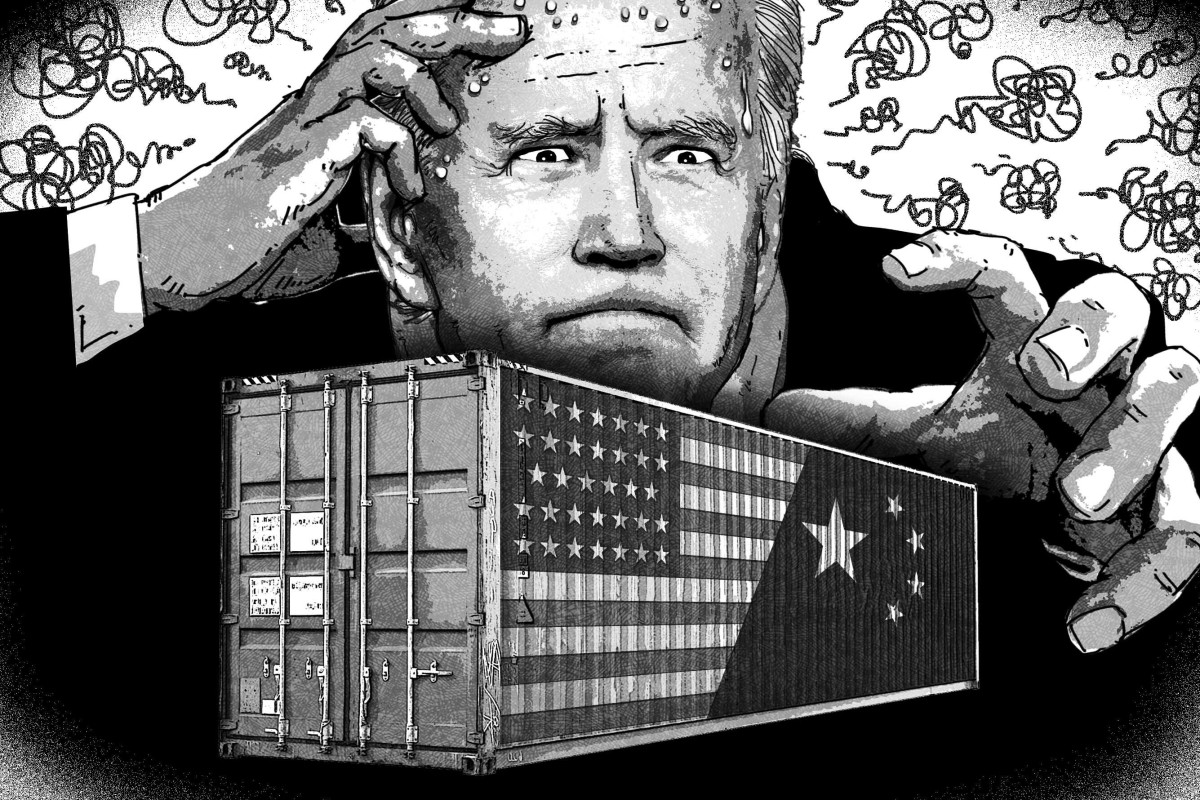

Joe Biden faces pressure to separate China trade policy from Donald Trump’s in US election

- Americans feel more negative about China than ever before, yet healthy trade ties with the world’s No 2 economy remain surprisingly popular among US voters

- Biden faces challenge in differentiating his China trade policy from Trump’s, with ex-White House aides expecting tactical changes rather than an overhaul

|

Biden “would re-evaluate the tariffs upon taking office”, the aide insisted, and had not in fact committed to removing them. But the scramble to counter the suggestion that he might be weak on China – or weak on trade – shows the challenges Biden faces in running against an antitrade, anti-China incumbent.

“Oftentimes candidates will be critical of trade, that is a very common tactic on the campaign trail. President [Barack] Obama, for example, when he was on the campaign trail in 2008, was critical of the way the United States had done trade deals,” said Elizabeth Baltzan, principal at American Phoenix Trade Advisory Services and a US trade official under Obama and President George W. Bush. “But we’re now seeing a very unusual situation in that it is the sitting president who is so critical of trade.”

This tightrope Biden must walk appears even more fraught when looking at how Americans think about both issues in 2020.

Pew research from July shows that a record 73 per cent of Americans now hold an unfavourable view on China, yet 51 per cent want to broker a strong economic relationship with America’s greatest modern-day rival.

A Gallup poll from February – importantly taken before the ravages of the coronavirus pandemic – showed that 79 per cent view trade in a positive light, a surprising figure, if one only judged the nation by its political campaigns.

One of Biden’s major challenges should he gain the keys to the White House will be synthesising these divergent views into coherent policy. He must unite a polarised nation, but also a broad church of Democrats, many of whom have also had enough of freewheeling commerce and perceived acquiescence on China.

“Policymakers must move beyond the received wisdom that every trade deal is a good trade deal and that more trade is always the answer,” wrote Jake Sullivan, a campaign adviser tipped by many for a senior role in a potential Biden administration, in a recent article for Foreign Policy. “The details matter.”

How I would frame it if I were Biden is: what can I do on trade, rather than what should I do?

The writings of Sullivan and others expected to be involved in a potential Biden administration have been key to understanding the direction the candidate may travel on both China and trade.

Figures such as Kurt Campbell and Ely Ratner – senior officials in the Obama administration – have been issuing mea culpa on both counts for months, admitting the China threat was underplayed in the past, while preaching that free trade needs to be pursued in a less gung ho fashion.

On China, the common theme has been the need to compete on some fronts and cooperate on others, stopping short of the zero sum view of trade policy that has defined Trump’s approach.

“How I would frame it if I were Biden is: what can I do on trade, rather than what should I do?” said former under secretary for commerce Frank Lavin, who was among the signatories to a “statement by former Republican national security officials” that ran in newspapers last week endorsing Biden.

“My view is he is going to retain some elements of Trump policy, but he certainly will not retain the harsh tone and the sort of combative rhetoric. So just that will be an improvement,” he added.

A recent Biden proposal to “rebuild US supply chains”, which name-checked China 10 times, with Russia the only other country named (three times), emphasised this fact.

“I think the real differences are going to be tactical. The main complaint the Biden camp has about Trump’s trade policy is that the US has picked a trade fight with allies rather than focusing ammunition on China, and it’s unnecessarily alienated countries that the US ought to remain close to,” said Edward Alden, a trade policy expert at the Council on Foreign Relations.

With that in mind, Biden would be expected to drop the controversial section 232 tariffs on aluminium and steel which were levied on allies from South Korea and Brazil, to Canada and the European Union. Whether China-specific section 301 tariffs remain in place may depend on China’s reaction to a new president, former officials have said.

“Those 232 tariffs are easier to dismiss than the China-specific section 301 tariffs. I think that is a little bit more difficult,” said James Green, who spent more than five years as Obama’s minister counsellor for trade affairs in the US Embassy in Beijing.

Green would expect China to test Biden on trade early on, perhaps discarding the phase one trade deal – which Green described as “the bamboo deal because it is Chinese on the outside and hollow on the inside” – then gauging the new president’s response.

“And so even if the Biden administration is not super excited about the trade tariffs, I think they’re going to be put in a position where they’re going to either have to walk away from them or double down on them,” Green said.

Keeping Trump’s tariffs in place would be a break from Biden’s previous rhetoric on trade. As a senator, he voted to normalise trading relations with China, including support for China’s accession to the World Trade Organisation, and endorsed the North American Free Trade Agreement.

When campaigning for the Democratic nomination, he said that “America’s farmers have been crushed by [Trump]’s tariff war with China”, adding that Trump “thinks his tariffs are being paid by China. Any beginning econ student at Iowa or Iowa State could tell you that the American people are paying his tariffs”.

“I would work with our allies in Europe and Asia to confront China on its troubling trade practices, not perpetuate Trump’s failing tariff war that is being paid for by hard‐working Americans,” she said, when campaigning in the Democratic primary.

If you look at some of the Democratic criticisms of the way Trump has gone about the tariffs, it’s not so much the tariffs themselves, it’s that they feel he has gone about it in an inadequately thoughtful way.

Should the pair win the election, some expect the tariffs to be reviewed, with those perceived to harm Americans most being discarded.

“I could see him undertaking a review of the tariffs and figuring out which ones are actually going to promote his goal of restoring US manufacturing and which are not,” said former US trade official Baltzan. “If you look at some of the Democratic criticisms of the way Trump has gone about the tariffs, it’s not so much the tariffs themselves, it’s that they feel he has gone about it in an inadequately thoughtful way.”

But there may be less room to manoeuvre on some of Trump’s other China-focused trade policies, such as the removal of Hong Kong’s special trading status, sanctions on city and mainland officials over the national security law, export controls on sensitive technology, along with embargoes and sanctions related to China’s human rights abuses in Xinjiang.

|

| Add caption |

Washington’s hardened position on Beijing’s claims in South China Sea heightens US-China tensions

Biden would almost certainly be more predictable than Trump. He would seek to rebuild alliances with scorned partners, at a time when China has fallen out with Australia, India, Canada and is struggling to make progress on an investment treaty with Europe.

“China may simply be taking advantage of the chaos of the pandemic and the global power vacuum left by a no-show US administration. But there is reason to believe that a deeper and more lasting shift is under way. The world may be getting a first sense of what a truly assertive Chinese foreign policy looks like,” wrote Kurt Campbell, a Biden adviser who was one of the architects of Obama’s “Pivot to Asia” policy, in a recent piece in Foreign Affairs.

But analysts on Chinese politics are divided on whether a return to multilateralism and pursuit of a coalition of allies will strike fear into the corridors of power at the Zhongnanhai leadership compound in Beijing.

“Beijing would still prefer Trump over Biden, because Biden lacks a unique personality guiding China policy. That means he would represent the consensus of the two American parties,” said Wu Qiang, an independent political analyst in Beijing. “Biden said he would improve relations with allies, something Trump has not done this past four years.”

Trump is destroying America, but he is destroying China too – he is destroying the whole world … so it is not good for China in the long run

This was a widely-reported view before the nosedive in US-China relations through the pandemic, that Beijing would rather deal with a transactional president than one who pushed for deep-rooted reform. But with Trump getting more hardline on China every day, and the relationship now in tatters, others are less sure.

“It is a common view among Chinese colleagues that yes, Trump has been very bad for China, but it could be worse because he has mainly focused on economic issues, and he is destroying America and its Western alliance, which will help China in the long run,” said Suisheng Zhao, director at the Centre for China-US Cooperation at the University of Denver, who thought that Beijing would now prefer a more conventional opponent in Biden.

“But I have told them that this is totally wrong, even from a Chinese perspective. Trump is destroying America, but he is destroying China too – he is destroying the whole world … so it is not good for China in the long run.”

The third story in the series explores the role of the Chinese Communist Party and how it represents a massive disconnect between Beijing and Washington.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.