Will Chile’s constitutional process satisfy its citizens’ thirst for democracy?

A new constitution that enjoys popular legitimacy promises to fix a profound political crisis in Chile, but its success will depend on its ability to widely represent citizens.

|

Simon Escoffier29 September 2020

On 25 October, Chile will hold a referendum that will decide whether the country will draft a new political constitution. A new constitution that enjoys popular legitimacy promises to fix a profound political crisis that led to five months of protests in late 2019 and early 2020, and has severely aggravated the country’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, we argue, the success of this constitutional process will depend on its ability to widely represent citizens.

Protests and unmet demands

The protests that started in October 2019 were unprecedented because they had huge youth engagement (55% of people aged 18-24 participated in at least one protest), were leaderless, cut-across classes and ideologies, and involved unseen levels of violence. Centred on the rejection of the “abuse” of the elite and the state, multiple demands coalesced in these mobilizations. Many protestors came from a large, diverse group of organizations with longstanding demands and involvement in demonstrations that can be traced back to the early 2000s. While their demands point to issues in health, education, housing, jobs, and pensions, they all unveil an ineffective social protection system co-opted by economic interests.

Since Pinochet’s dictatorship in the 1980s, the Chilean state has, for example, insistently weakened its public schools to benefit the private sector. In fact, 60% of pupils currently attend some sort of private school, which means that the majority of students pay tuition to institutions in order to obtain education.

Protestors have also called for an urgent pension reform. Introduced by the Pinochet regime, pensions in Chile are mainly characterised by compulsory workers’ contributions managed by the for-profit Administrators of Pension Funds (AFPs for its acronym in Spanish). Although workers put in around 10% of their salary per month, their pensions end up being extremely meagre: 80% of pensioners receive less than the minimum wage of US$ 408 each month, with women being particularly affected.

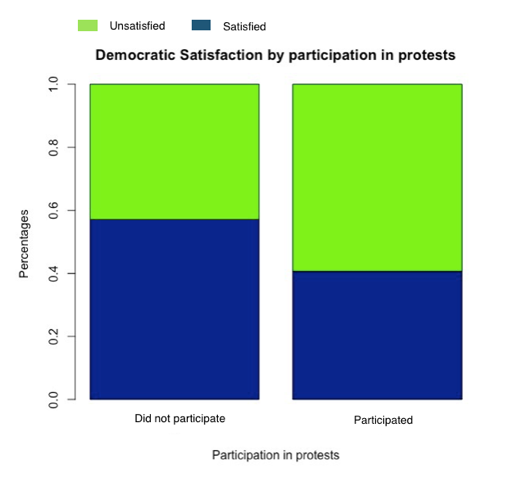

Once and again, authorities have shown to be reluctant or slow in reacting to people’s demands. Which is why, since October 2019, protestors demonstrated to be disproportionately disappointed with their political regime (see Chart 1).

Chile’s political crisis

In 2014, the Chilean tax authorities uncovered a network of politicians that illegally funded political campaigns with contributions from a mining company called Soquimich. The fraud amounts to US$6.6 billion and cuts across the political spectrum, involving politicians from the two main political coalitions. A pardon was then devised by the Bachelet government to prevent politicians facing corruption trials. Since then, similar scandals have involved other politicians, the Catholic Church, the military and the police.

These scandals add to Chileans’ mounting sense of frustration with their elites. The result is Chile’s high political disaffection. Since its democratic transition in 1990, the country’s divorce between people and political institutions has widened progressively. According to yearly polls, the highest level of trust in the parliament and political parties between 2015 and 2019 was a meagre 6%. In 2019, in fact, an abysmal 2% of Chileans said they trust politicians. Similarly, while 44% of people declared having no political identification in 2006, that number soared to 72% in 2019.

This is then reflected at election time: Chile suffered the sharpest fall in electoral participation among the world’s democracies, from 86% in 1989 to just 46.6% in 2017, meaning that a majority of the population did not vote in the last presidential election. Because the rich tend to vote at higher rates than the poor, this translates into political inequality, where the voices of the least well-off count less, further reinforcing feelings of political inefficacy and apathy.

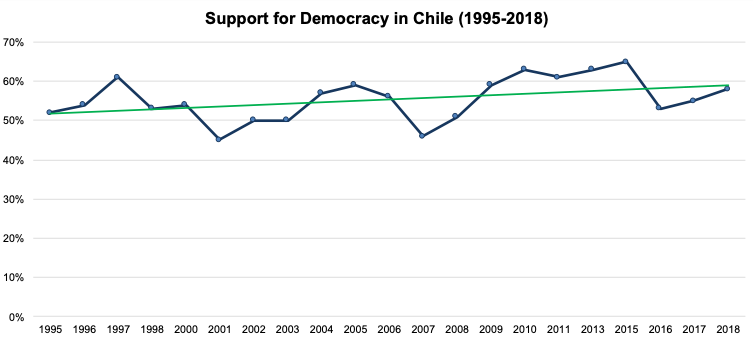

Yet, despite people’s sustained disconnection from institutional politics, a growing number of them support democracy (see Chart 2). In other words, citizens’ dissatisfaction with political authorities is in part the result of them wanting a more democratic system – one that responds less to elite interests and more to people’s needs.

A new constitution: More democracy?

One of the most important legacies of the dictatorship is Chile’s current political constitution. Although it has suffered many amendments, the core contents of the document have remained the same since it was undemocratically approved in 1980. The constitution is, therefore, widely unpopular.

It also strongly undermines Chilean democracy. The document, for example, establishes a politically elected Constitutional Tribunal that can veto legislation already approved by parliament. This tribunal has insistently favoured pro-business and pro-elite legislation. The constitution also makes it almost impossible to change a group of Organic Laws that are key to the country’s political structure. These laws regulate Chile’s highly centralized administrative state system, the almost complete autonomy of the armed forces and political parties’ strongly concentrated power structures. They also regulate the commodification and financialization of Chile’s pension system. In addition, the constitution erodes social rights by giving private investors priority over the state’s service provision.

Chileans have long considered their constitution illegitimate and understand how central a new Magna Carta is for their country’s future democratic development. Facing the violent political crisis that erupted late last year, the Chilean parliament decided to begin a constitutional process that could redraw political engagement. As a result, a national referendum will be held on 25 October 2020 to decide whether the country needs a new political constitution and on the method to achieve that goal – either through a Constitutional Convention (CC) or a Mixed Constitutional Convention (MCC). While the MCC will be composed by citizens and members of parliament (86 of each), the CC will only include elected citizens (155).

Polls indicate that the vast majority of the population will approve a new constitutional process and will choose the CC as the method to draft the new document. These decisions presumably prevent the political and economic elites from controlling the process. Furthermore, after tireless lobbying, a group of academics and activists were able to secure gender parity for the CC, which is a substantial step in making it more representative.

Unfortunately, however, despite these electoral arrangements, a set of factors makes it unlikely that this process will properly satisfy the population’s thirst for democracy. First, the D’Hondt system planned to be used to elect CC and MCC members makes it almost impossible for independent candidates to get a position. In other words, the constitutional process will exclude community leaders and other citizens who are not affiliated with any political party.

Many key decisions in the constitutional draft may be influenced by the already highly unpopular party elites, eroding the new constitution’s popular legitimacy. Second, no quotas for indigenous people have been defined in the CC or the MCC. This means that the historically marginalized and already politically underrepresented indigenous population will also have their voice undermined in Chile’s new constitution. Several organizations, activists and political figures have called attention to these matters. Authorities still have time to secure a properly democratic political constitution for Chile. Wasting this historic opportunity would mean betraying citizens’ hopes and expectations, detaching them from the political process even further.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.