The Balfour protests helped to topple Netanyahu. But at what cost?

Even if the next government is worse, the anti-Bibi protests show that when enough people mobilize around a single message, they have a chance to win.

|

By Meron Rapoport December 23, 2020

A single slogan can summarize the anti-Netanyahu protests that have been taking place across Israel over the last half year: “It won’t end until Netanyahu goes.”

Netanyahu may not have quit, but the Knesset effectively decided to fire him on Tuesday night when it refused to give him more time to pass the annual state budget, thus dissolving itself. New elections — the fourth round in less than two years — will take place on March 23, 2021.

And thus, the protest movement won the rare achievement of actually achieving its goal: the overthrow of the Netanyahu-Gantz government.

The demonstrations — an extension of the regular protests that previously took place outside the home of Attorney General Avichai Mandelblit, calling on him to indict the prime minister for corruption — began in earnest this past March, when former Knesset Chairman Yuli Edelstein tried to prevent the election of a new chairperson to the parliament. As Israel went into nationwide lockdown during the first wave of COVID-19, hundreds of protesters drove to the Knesset to prevent what was being labeled a “constitutional coup.”

The moment Benny Gantz decided to forgo the possibility of becoming premier and instead join Netanyahu was the moment the so-called “Balfour protests,” named after the street of the prime minister’s residence, were born.

|

Much criticism has been lobbed at the protesters for focusing solely on Netanyahu. But even critics must now agree that at the end of the day, the targeting of the prime minister worked.

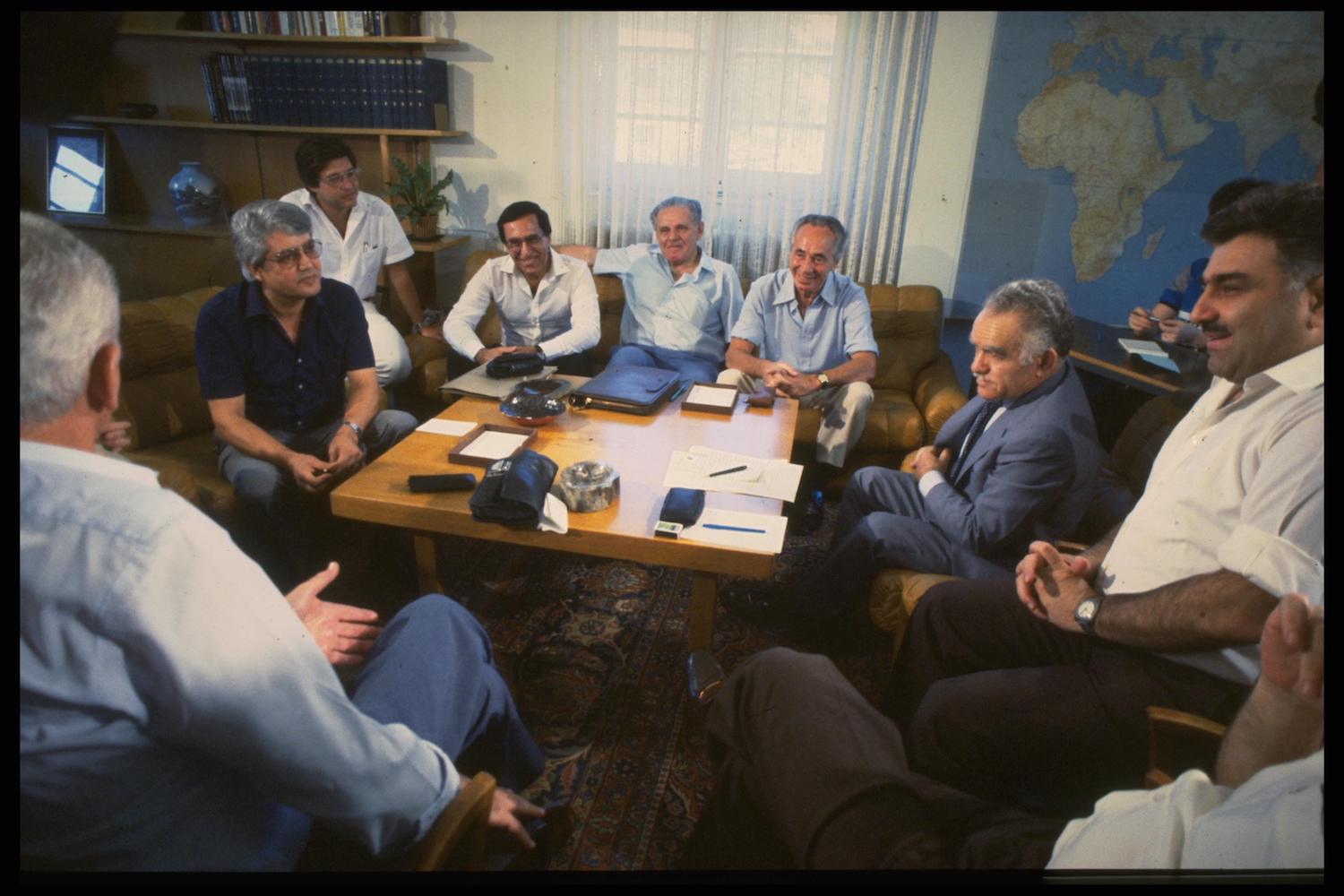

It is difficult to believe that this government would have reached the end of its road without the protests. Unity governments have been formed in Israel since the 1980s, when tensions between the right and the left were perhaps even more acute than today. Even if there were those on the radical left who ridiculed the attempts of Shimon Peres’ Labor Party to create “change from within” by joining Yitzhak Shamir’s Likud, it did not lead to any major protest movement.

Even Netanyahu’s second and third governments — the ones he formed in 2009 and 2013, respectively — were a kind of unity government that included political opponents from across the aisle in top cabinet positions. In this context, the comparison between the 2020 Balfour protests and the 2011 social justice protests is particularly striking.

|

The central slogan in 2011 was “The people want social justice.” The 2020 protests were more modest. They did not pretend to speak on behalf of the “people,” since it was clear from the outset that considerable segments of Israelis support Netanyahu. It therefore set the threshold far lower and set its sights on ousting the prime minister.

The 2011 protest did not achieve “social justice” for Israelis. Yair Lapid, who rode that protest wave all the way to the Knesset with 19 parliamentary seats, was not ashamed to sit in the Netanyahu government, and no one took to the streets to protest, as happened to Gantz from the moment he joined the prime minister. It is clear which of the two movements was more effective: the protests did not give Gantz the same space for maneuvering that Peres enjoyed in the 1980s or Lapid had in 2013.

Some of this is of course hypothetical, but one can safely assume that without the protests on Balfour Street, Gantz would have let Netanyahu off the hook. It is not for nothing that Gantz has repeatedly stated that freedom of protest should be protected, even during a pandemic. He had no other choice.

|

According to reports, Gantz was prepared to surrender to Netanyahu and curb the powers of Justice Minister Avi Nissenkorn, a member of Gantz’s Blue and White party, as part of negotiations to keep the current government afloat (one of Likud’s core demands has been to fire Nissenkorn in order to prevent him from appointing a state attorney and attorney general, two positions viewed as critical to Netanyahu in his criminal trial). The protests outside Gantz’s home made clear that this would not pass quietly. They also showed Nissenkorn and other Blue and White party members who opposed the Netanyahu-Gantz deal that they have support and therefore have no reason to fold.

The protests’ effect also went beyond Blue and White. Gideon Sa’ar — who quit Likud to start his own party and currently poses the biggest threat to Netanyahu’s rule — will certainly not admit it, but it would have been impossible to imagine him as a real contender for prime minister without the atmosphere created by the protests.

Israel has seen many influential demonstrations over its 72 years of existence, from the Wadi Salib uprising to the Israeli Black Panthers’ protests to Land Day to the First Intifada. But when it comes to effectiveness — that is, the relationship between the protest’s stated purpose and its outcome — the Balfour protest can perhaps only compete with the 1973 protest of Motti Ashkenazi, who led a movement after the Yom Kippur War that led to the resignation of Prime Minister Golda Meir’s government.

|

Ashkenazi’s protest, which targeted Meir and Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, led to their ouster; but it also came after a national trauma and more than 2,600 deaths. The anti-Netanyahu protests appeared after the attorney general filed an indictment against a prime minister. A serious event in and of itself, but by no means comparable to what happened to Israeli society in the 1973 war.

The Balfour protesters are not the Bolsheviks in 1917: they have no plan to conquer the Winter Palace and seize power. After this current government falls, the next government will be determined at the ballot box — which means that there is a chance that if Bibi finally goes, the protest movement will disappear as well.

There are signs that this will not happen. During the six months of its existence, the movement developed certain elements that seek to rethink and challenge the concept of Israeli democracy itself. There are voices that spoke out against police and military violence toward minority groups and the occupation. The new spirit that was created by the protest, along with the thousands of activists who were educated by it over the last half year, will not disappear so quickly.

It is also possible that right-wing reactionary elements, such as Sa’ar, Naftali Bennett, and Avigdor Liberman, will enjoy the fruits of the protest. If we believe the polls, it is quite likely that the next government will be a right-wing one, perhaps even worse than the current one.

But even if that happens, the anti-Netanyahu protests should teach us one thing: once enough people put forth a single clear message, there is a chance they will succeed.

If opponents of the occupation had managed to mobilize even 5,000 protesters every week, the occupation would not have been able to continue resting on its laurels. If unions had managed to besiege the Finance Ministry on a weekly basis, Israel would not be lagging behind the rest of the world when it comes to the social services it provides to its citizens.

In this sense, even if the Balfour protest ends only in the overthrowing of the government and forcing of new elections, it will be remembered as the movement that taught Israelis an extraordinary lesson in civics. For that it deserves praise.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.