How women of Isis in Syrian camps are marrying their way to freedom

|

by Bethan McKernan , Vera Mironova and Emma Graham-Harrison-Fri 2 Jul 2021

Hundreds of foreign women with links to Islamic State in Syria’s sprawling al-Hawl detention camp have “married” men they met online and several hundred have been smuggled out of the facility using cash bribes gifted by their new husbands.

The camp’s inhabitants have been sent wire payments totalling upwards of $500,000 (£360,000), according to testimony from 50 women inside and outside Hawl, local Kurdish officials, a former Isis member in eastern Europe with knowledge of the money transfer network and a foreign fighter in Idlib province involved in smuggling.

The practice is a significant security risk inside Syria and for foreign governments who refuse to take their nationals home – but according to many interviewees, getting married is both easy and an increasingly popular escape method.

|

“Every day I get a man texting me asking if I am looking for a husband,” said one woman from Russia living in the camp. “Everyone around me has got married … although those who are still pro-Isis and pretend to be modest would deny it.”

Approximately 60,000 women and children who poured out of Isis’s last Syrian stronghold when the so-called caliphate fell in March 2019 are now detained in Hawl by the US-backed Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which control the north-east of the country.

Their imprisonment is a rallying cry for Isis supporters across the world, and “marrying” one of the imprisoned women – even in a long-distance, online relationship – has become a badge of honour on the jihadists’ social media networks.

For men, it is a way to raise their social standing and help those in need. Most prospective husbands appear to have roots in Muslim countries but live in western Europe, where they are relatively well-off.

For the women of the camp, it is a way of securing an income that can make life in Hawl more bearable: the money is used for daily necessities such as nappies, food, medicine, phone credit and to pay other women to cook and clean.

-

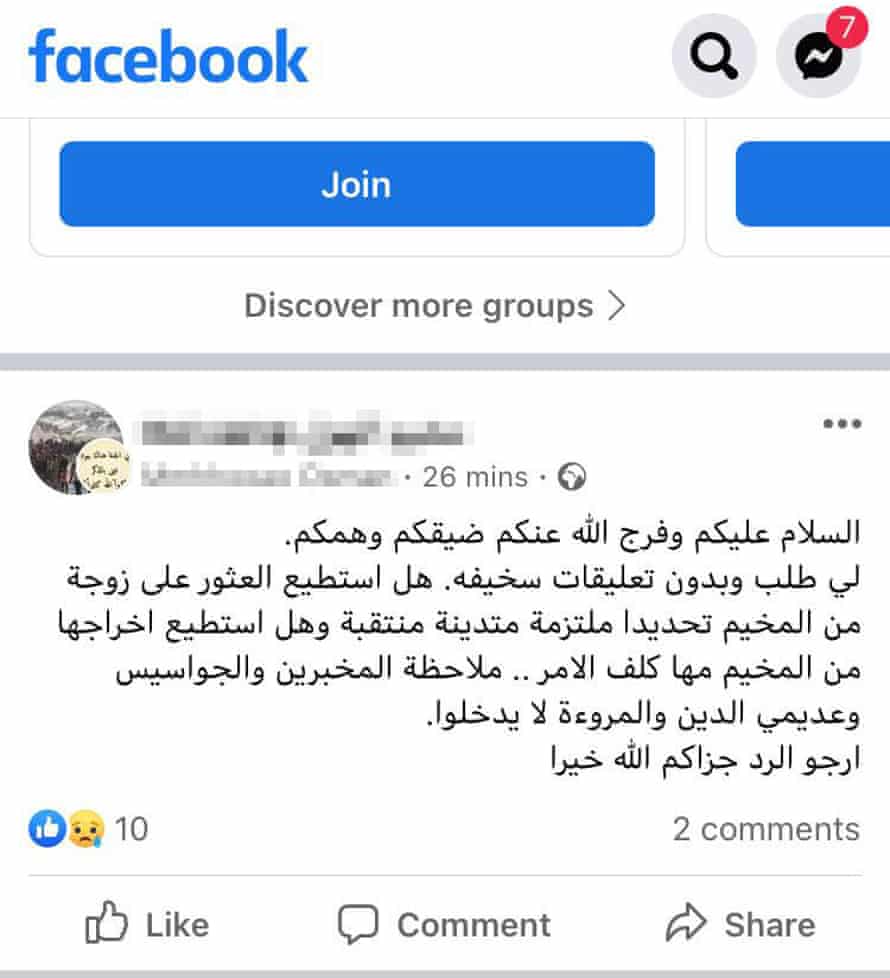

Left: a Facebook post in Arabic reads: ‘I have a request … Can I find a wife from the camp committed to religion … I can get her out no matter the cost.’ Right: post by a Spanish woman in the camp

“I have a request … ” reads one of dozens of similar Arabic language posts on an Isis-friendly Facebook group concerning the camp. “Can I find a wife from the camp committed to religion … I can get her out no matter the cost.”

There are no official estimates for how many women have managed to leave Hawl in this manner. But when Isis-affiliated families first arrived at the camp two years ago, there was little space and families had to fight for tents and resources. Now, some foreigners have been moved to another camp and some have escaped, leaving several rows of the annex housing foreigners totally empty.

It is not clear where most of the escaped women are now, but one woman the Guardian spoke to is now living with her new husband in the former Soviet Union.

How it works

The “marriages” are conducted over the phone. Usually it isn’t necessary for the woman to be on the call: a mediating sheikh says a few verses and then pronounces the groom as her new wali, or guardian, and the bride then receives cash or a new mobile phone as a dowry.

Many of these virtual relationships appear to be charitable in nature, but flirtatious messages and pictures seen by the Guardian suggest some are romantic or sexual. A fighter in Syria’s Idlib province who was killed last month was found to have exchanged sexually explicit messages and pictures with women who said they were in Hawl, according to a source who checked the man’s phone after his death.

Some of the women’s real husbands are still alive in SDF prisons, but they claim they are free to marry because they cannot be sure their husbands are Muslim any more. If their new husband does not deliver on his promises, some are willing to get married more than once.

“My ex-husband promised to support me but then said that he has problems with his job or maybe he was just afraid to send money and get arrested, so I broke up with him,” said one woman in the camp. “I’ve met another guy online now that I am considering marrying, but he is young, so I am not sure he would be able to support me and my kids.”

The hard part is making a union physical. Getting out of Hawl can cost up to $15,000, depending on nationality, how many children are involved and which smuggling method can be afforded.

Escapes are usually organised by brokers in Idlib, the last area of Syria that remains outside the control of the president, Bashar al-Assad – the Kurdish-held north-east has an uneasy, but currently non-violent, relationship with the regime. The operations are arranged along ethnic and linguistic lines: a Russian-speaking broker, for example, will usually only deal with other Russian speakers.

The most expensive way out is by private car, bribing both SDF and Islamist checkpoints until reaching an Idlib safe house. The next best way is to hide in water tankers, buses or other vehicles that enter the camp, with the knowledge of the driver. The cheapest option is to walk out after paying off the guards, or to make a run for it during the night.

-

SDF special forces keep watch in the vicinity of al-Hawl camp in March

The SDF is aware of the scale of the problem, and that guards and workers at the camp are either willing to take bribes or are coerced into helping with escape attempts. “Some of the [pre-existing] Isis smuggling network is still operating, but regarding al-Hawl, I think most of them are opportunists: people that are provided with money or face threats,” said Kino Gabriel, an SDF spokesperson.

“One of the truck drivers providing water for the camp was involved in smuggling weapons inside. Eventually he failed, or they were discovered, we don’t know. But a few days later, he was shot.”

The money trail

Hawl was already a miserable place, but since the families of Isis fighters arrived it has become a breeding ground for extremism and criminality. Outnumbered SDF guards have struggled to keep control: guns and knives are now common inside the camp, with 40 murders committed since the beginning of 2021, according to local officials. Seven women in the foreign annex beat and attacked each other with knives last week, and one beheading attempt was made.

Many governments, including the UK’s, are reluctant to repatriate the 9,000 foreign nationals and their children living in Hawl and many women are aware they may face imprisonment at home. If they do not want to wait for Isis to rise again and free them, or have decided they are no longer loyal to the group, the alternative is to raise enough money to bribe guards and leave under their own steam.

Several women in the camp estimated that true extremists only made up about 20%-30% of its inhabitants. It is nearly impossible to tell, however, because so many will talk or act in performative ways in order to attract funding on jihadist social media networks.

|

-

Al-Hawl camp in February 2019

The most obvious way for sympathisers to help is by sending cash. Isis supporters around the world, and the inhabitants’ families, send money for daily necessities, which arrives at one of two hawala, or informal wire transfer services, at the camp.

For many families, the priority is boys, who once they reach puberty are supposed to be sent to SDF-run “deradicalisation centres” – in reality, little more than prisons. Rather than risk that, mothers will pay bribes to the guards in order to get their sons out of the camp.

The easiest way of getting a steady income, however, is to find a husband.

Every “marriage” follows the same pattern: a woman in Hawl sets up a profile page on Facebook or Instagram, posting pictures of lions and other Isis-affiliated iconography, and calls on the Muslim community to save her. Explicitly radical content or conversations with potential husbands can then move over to Telegram, an encrypted app, where it is more difficult to detect terrorist activity.

Husbands send money directly to Turkey via normal wire transfer, or if they are afraid of being detected, a receiver in a second country: from western countries, usually the Balkans or Ukraine. From there, the money goes to Turkey, where it will cross the border as cash, or is sent by hawala directly to Syria.

In February, members of an Isis cell in Kyiv were arrested after a police raid discovered $13,000 in cash and accounting books recording large amounts of money collected online and then sent to Syria, according to a source with knowledge of the operation.

“The fundraising campaigns often look innocuous at first: to figure out whether they are collecting money for Isis-affiliated families, or possibly the group, you have to follow which accounts are sharing it or liking it on social media. Understandably, it can take a long time for service providers and analysts to identify and distinguish this activity,” said Audrey Alexander, a researcher and instructor at the Combating Terrorism Center at the US military’s West Point academy.

“It’s the same for governments. In the US, for example, the Department of the Treasury appears to have some good insights into some of the major players and actors in these networks and can issue [terrorism] designations. But those measures affect only a few hubs in a complex web of facilitators.”

Life after Hawl

Almost everyone who leaves Hawl heads to Idlib province, 400km (250 miles) away. The other option is to join Isis sleeper cells in the eastern desert of Deir ez-Zor: according to women in the camp, at least one group of Uyghur teenagers has managed to do so after leaving Hawl.

Idlib is for the most part ruled by a rival jihadist group known as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) but the chaos and poverty in the area makes it easy for Isis to maintain safe houses. The group’s former leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was sheltered there at the time of his assassination in 2019 by a smaller jihadist group also at war with HTS.

Some escapees will stay in Idlib, either biding their time until the “caliphate” rises again, or to live with HTS fighters who believe they can reform the Isis women, having sent money to rescue them from Hawl.

Idlib also borders Turkey. For those who want to make it back to their home countries, or join new husbands elsewhere, trying to cross is very dangerous, but possible, with a lot of luck. Fake passports are purchased once over the border.

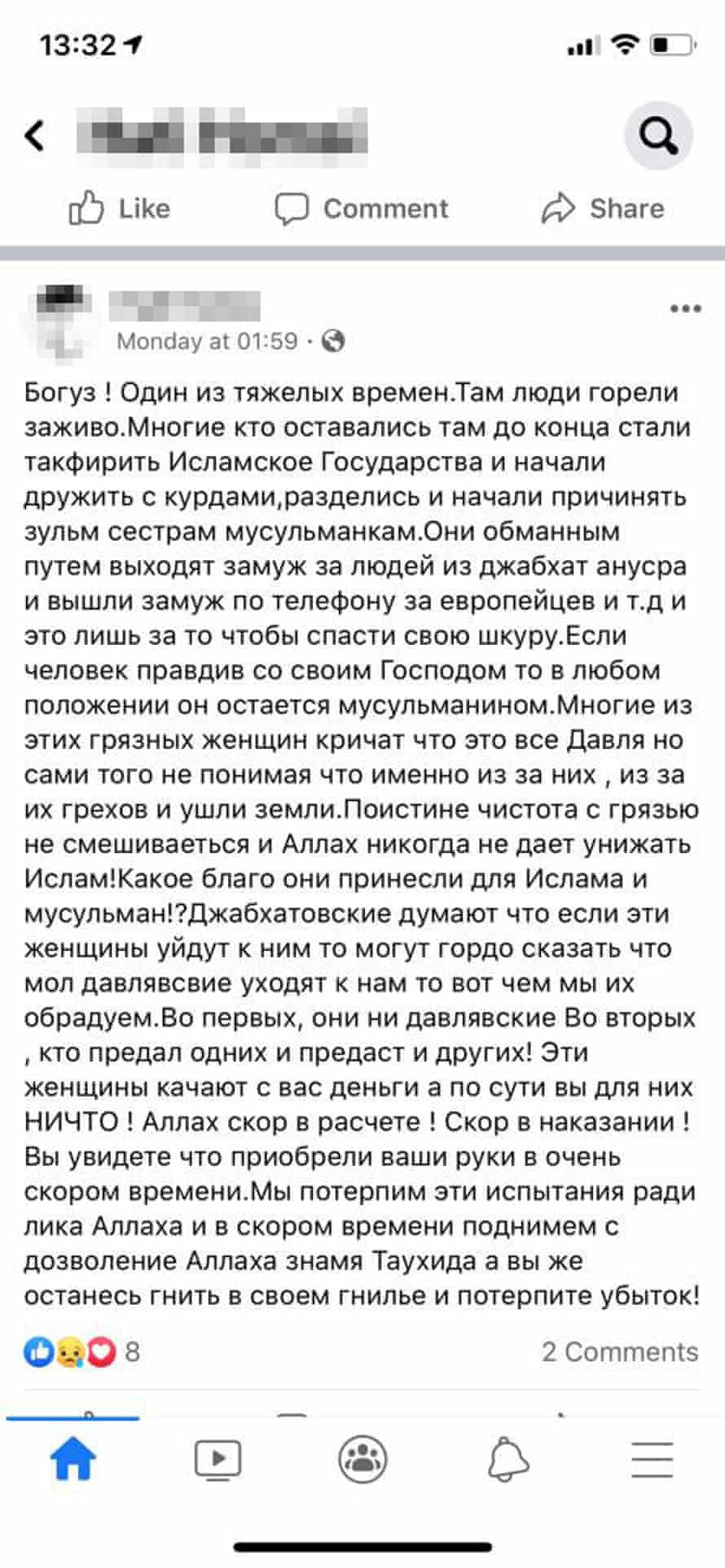

The influx of Isis-affiliated women in Idlib is not just a security concern for HTS: the new arrivals are also causing familial conflicts. In Facebook tirades, the wives of men who are communicating with women in the camp openly call the Hawl women prostitutes and say the camp is a brothel.

![Message from Russian woman living in Idlib: ‘These women flirting make men love them and be all over them [literally: hang on their necks]. They are making fitna [unrest, rebellion] in families ... I have many complaints from sisters ... One woman even went to hospital after she was beaten by her husband after he had a haram talk with one of the camp girls. Women know this is fitna for men. Yet they use them, play at love, but it’s not real love.’](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/90516e2be2aeab73832d7505005603971eac10a7/0_0_473_1024/master/473.jpg?width=445&quality=45&auto=format&fit=max&dpr=2&s=f21b4894ada2fd24655acb3fe82836b0)

-

Left: post by a pro-Isis Russian woman in the camp: ‘Baghuz [the fall of Isis in Syria] was one of the hardest times. There were people burning alive ... many who stayed to the end became takfir [not Muslim] and became friends with the Kurds. They got naked [not literal, she means taking off their hijab] and started doing harm to Muslim sisters, marrying people from Jabhat al-Nusra [former name of HTS] and Europeans on the phone just to save their asses ... These dirty women don’t understand it’s because of them we lost the caliphate ... Those who betray once will betray again. Those women will pump money from you but in reality you are NO ONE to them. Soon you will see what you have on your hands.’ Right: message from Russian woman living in Idlib: ‘These women flirting make men love them and be all over them [literally: hang on their necks]. They are making fitna [unrest, rebellion] in families ... I have many complaints from sisters ... One woman even went to hospital after she was beaten by her husband after he had a haram talk with one of the camp girls. Women know this is fitna for men. Yet they use them, play at love, but it’s not real love’

According to one female former Isis member, who now lives in Idlib and is married to a foreign fighter with HTS: “Girls from camps write to my husband and try to flirt with him ... I am very pissed at them since they are intentionally trying to break up our family.”

After one woman “married” her new husband by phone and then immediately left him once she arrived in Idlib, boasting about her ruse on social media, some HTS affiliated groups issued orders telling men not to rescue women from the camp. But according to women inside, the practice has carried on unabated.

As long as the camps exist, so too will the flow of money in – and the flow of people out.

Some will be driven by radical ideals; some are just desperate. Women who say they were forced into joining, as well as thousands of children, are also facing the prospect of languishing in Syria’s camps indefinitely.

Mehdia, a 22-year-old Uyghur woman, said she was taken to Syria by her husband when she was 17 and had no idea what awaited her. An escape attempt from Hawl last year was driven by desperation at the appalling conditions and funded by members of the Uyghur community in exile, rather than a new online husband.

She was driven out of the camp in a mini-van but was discovered the next day at an SDF checkpoint. “You have the people who are still radicalised in Hawl, probably they want to get out and to go to Isis,” she said. “But I don’t want to be in Syria at all. I have three kids… It’s not a good place for them.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.