The outspoken Azerbaijani writer exiled in his own country

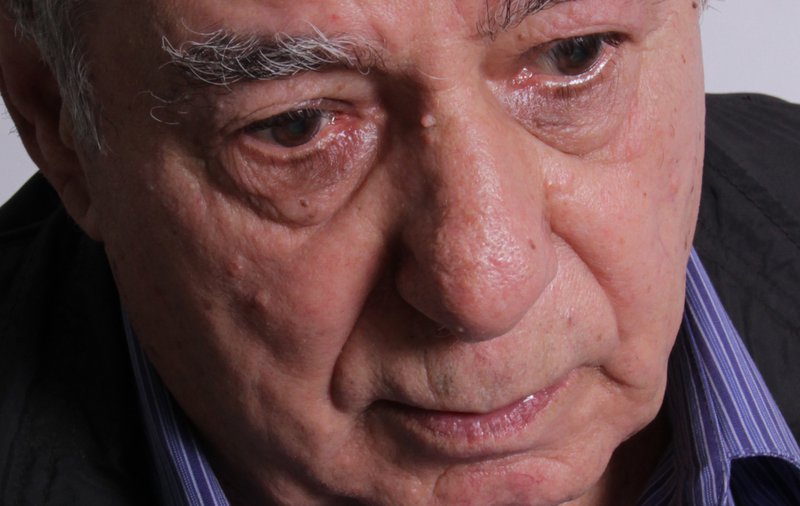

Every day an elderly writer sits in his apartment a few blocks from the Caspian Sea and reads – but only a little as his eyesight is poor.

His preferred reading is fantastical and satirical novels such as ‘Don Quixote’ and Mikhail Bulgakov’s ‘The Master and Margarita’. He just completed his own translation of another favourite, Salman Rushdie.

While he can step out of his apartment and walk down to admire the blue-grey sea, his physical world is limited to these streets.

Indeed, this writer’s life now resembles that of a surreal tale by his favourite authors. At the age of 84, Akram Aylisli is an outcast. He cannot leave Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, or visit his native village. He is isolated from old friends, family members and readers. His books have been burned and pulled from Azerbaijan’s libraries, theatres and schools. Mostly what remains, he says, is the life of the mind.

“For many years now, my only salvation from the dirt of the outside world is literature,” Aylisli told me in an email in August. “There is more air for me there than in the whole city of Baku.”

If the Azerbaijani government’s tactic has been to cut Aylisli off from the world, they have largely succeeded. In 2016 the writer, then aged 78 and already in poor health, had been preparing to fly to speak at a literary festival in Venice. But at Baku airport, he was detained by Azerbaijani police officers for allegedly assaulting a border guard.

Five years on, prosecutors have still done nothing to substantiate this bizarre charge (which technically means the case should be closed), and Aylisli’s travel and identity documents remain confiscated.

The dethroning of Aylisli, formerly the national writer of Azerbaijan, happened overnight in 2013. Protesters burned Aylisli’s effigy and held up a symbolic coffin outside his apartment block in Baku. In Azerbaijan’s second city, Ganja, a crowd built a pyre and threw his books on it. His wife was sacked from her job as director of a children’s library. One of his two sons lost his job and left Azerbaijan.

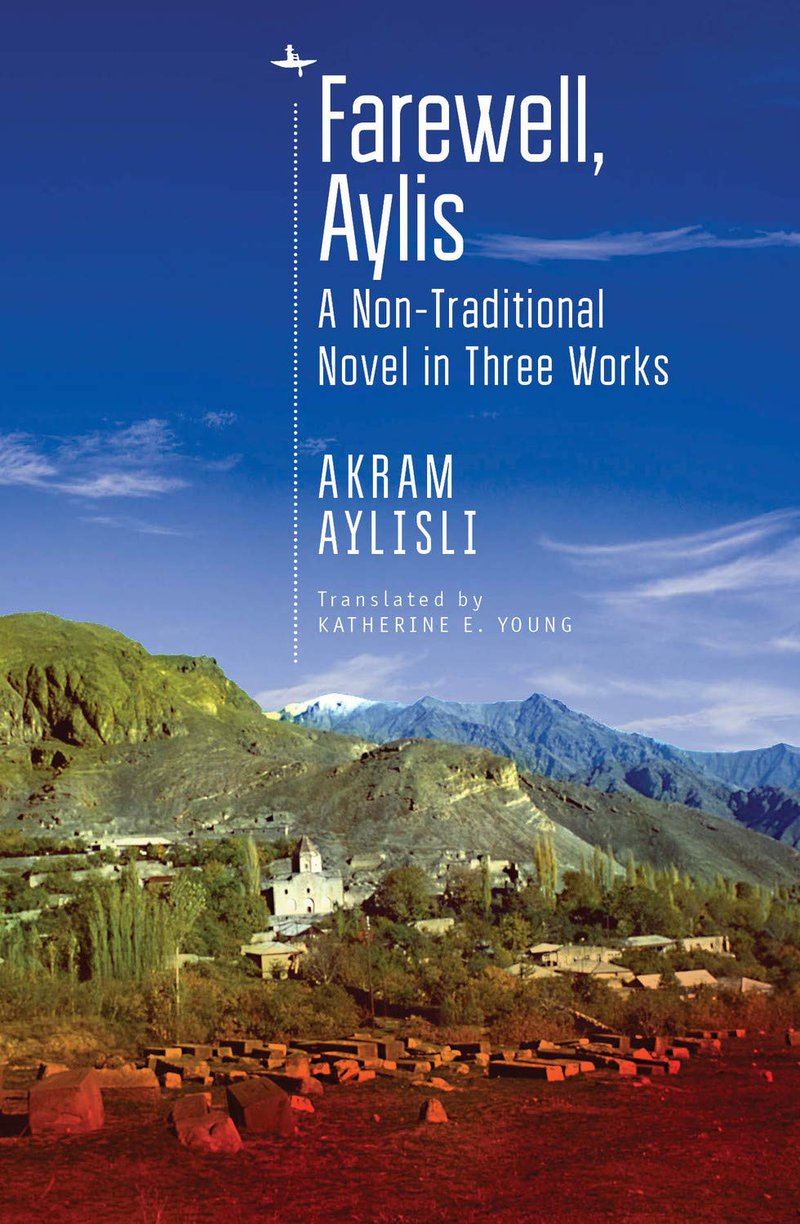

Aylisli’s crime? He had broken the central taboo of modern Azerbaijan when he published a novella. Its title: ‘Stone Dreams’.

Clear voice

Since the late 1980s a conflict at least as toxic as the Israeli-Palestinian dispute has consumed Armenia and Azerbaijan. In the early 1990s, fighting over the disputed mountainous territory of Nagorno-Karabakh claimed 20,000 lives and forced more than a million people to flee their homes. Each republic was almost entirely cleansed of the population of the other.

Official discourse allows no light and shade. In Azerbaijan, Armenia is presented entirely as an aggressor and occupier of Azerbaijani lands. Armenians routinely decry Azerbaijanis as inherently “genocidal” and barbaric. In reality, as in most ethno-territorial conflicts, both sides have committed crimes against the other, from the pogrom that killed peaceful Armenians in the Azerbaijani city of Sumgait in 1988 to the massacre of Azerbaijani civilians outside the village of Khojaly in 1992.

And yet, for long periods in their history, Armenians and Azerbaijanis have lived together harmoniously and share many common elements of culture and tradition. Everyone knows this, but very few in either country dare to say it out loud. Aylisli’s is the clearest voice.

Just over a year ago, on 27 September 2020, the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict restarted, ending an imperfect ceasefire that had lasted 26 years.

Over 44 days, the Azerbaijani army, with military assistance from Turkey, upended the defeats and losses the country had suffered in the war of the 1990s. They recaptured land that had been under Armenian military control for decades. As a result, thousands of Karabakh Armenians fled ahead of the Azerbaijani advance, before a Russian-brokered truce took effect in November.

Ceasefire

Azerbaijan reaped humanitarian benefits: its victory will potentially allow hundreds of thousands of its citizens, displaced in the 1990s, to return home. But the human cost of the war was huge. More than 7,000 people died, most of them young soldiers who were not even born when the first Karabakh war was fought.

Hatred and trauma were kindled in a new generation, as reports came in of prisoners executed and schools being bombarded.

Armenian and Azerbaijani social media overwhelmingly became platforms of hate and disinformation.

Briefly, there were hopes that the conclusion of the new war might bring serious political negotiations, a peace agreement and then state-to-state reconciliation. But official Azerbaijan is not in a generous mood towards its defeated rival.

Since the ceasefire of November 2020, Azerbaijan has kept dozens of Armenian military detainees captive and put them on trial, despite international calls for their release. Contemptuous anti-Armenian rhetoric continues unabated.

Space for peacemakers is limited. Aylisli’s voice has been drowned out by the noise, though he still hopes that his book, Stone Dreams, has had some influence on the discourse. “By publishing [the novel], I saved many Armenians from Azerbaijani hatred,” he wrote. ”I am proud of that and will be proud forever.”

Path from the village

Before 2013, there were only a few clues in Akram Aylisli’s biography that the writer would take such a stand.

He was born Akram Naibov in 1937. His father, a soldier in the Red Army, died when Aylisli was five, and the future writer grew up in poverty. He comes from the village of Aylis in Nakhchivan, a remote exclave of Azerbaijan which borders Armenia, Iran and Turkey. Once he became a writer he adopted the nom de plume Aylisli (“Akram of Aylis”) in honour of his home.

“The important thing to understand is that he grew up in a village,” Shura Burtin, a Russian journalist who has championed Aylisi both as a writer and a peacemaker, told me from St Petersburg. “He grew up in a different world,” said Burtin, suggesting that his humble, rural background conferred on Aylisli his distinguishing quality of “clarity,” both moral and artistic.

His home village of Aylis “is a huge character in all the books,” concurs Katherine Young, Aylisi’s English translator. She compares Aylisli’s recurring writing about his village to the literary strategy of William Faulkner, using one place to be “both minute and broad in the scope of what he writes”.

Aylisli studied in Moscow in the 1960s, during Nikita Khrushchev’s post-Stalin “thaw”. He was one of a group of writers with village backgrounds who wrote about rural life, breaking with the diktat to create socialist realist literature with boiler-plate heroes. His early works, especially a series of novellas entitled ‘People and Trees’ set in Aylis, earned him hundreds of thousands of readers in his native Azerbaijan and also in Russian translation. Aylisli single-handedly “created the lyricism of Azerbaijani prose,” says Jamil Hasanli, the Azerbaijani historian.

Compassion

Young, Aylisli’s English translator, notes how he marked himself out early by rejecting the traditionally patriarchal traditions of the Caucasus. Having lost his father as a child, he was brought up by women and in his work his strongest characters are women.

The dramatic topography and tragic history of Aylisli’s homeland of Nakhchivan was also formative. Its high mountains descend to the broad Arax river which runs for 1,000 kilometers between four countries.

In the early 20th century, Nakhchivan had a mixed Armenian-Azerbaijani population. Between 1915 and 1916, the Armenians of the Ottoman Empire were killed or deported in the Genocide, the worst atrocity of the First World War. Then, after the Russian empire fell apart, Armenians and Azerbaijanis pitched into conflict. The briefly independent states of Armenia and Azerbaijan fought over Nakhchivan. After the war the Allied powers briefly tried to make it a neutral protectorate. The Bolsheviks made it part of Soviet Azerbaijan in 1921.

The village of Aylis, which Armenians call Agulis, had a dozen Armenian churches and a large Armenian population as well as many Azerbaijani Muslims. That changed in December 1919, when Azerbaijanis and Turkish militias massacred most of its Armenian villagers.

The burned ruins of the Armenian church of Aylis were the backdrop to Aylisli’s childhood, but few talked about what had happened. An exception was his mother. “All my conscious life I carried compassion within me for the Armenians because, in very early childhood, my mother – a deeply pious Muslim, told me almost every day of the hideous atrocities which the Turks had committed in 1919,” Aylisli wrote to me.

In the Gorbachev era, this memory suddenly became relevant as Armenians and Azerbaijanis revived old quarrels, and violence broke out again. In 1989 Aylisli wrote a public letter to his colleague, Sergei Baruzdin, editor of the journal Druzhba Narodov (Friendship of Peoples), condemning the new nationalism and advocating dialogue. In the letter he confessed to feeling a “suffocating loneliness” as so few other Armenian or Azerbaijani intellectuals shared his stance.

Letters to the president

After Azerbaijan became independent, Aylisli made an accommodation with the new regime. In 2005 he was elected to parliament as a deputy from his home region. Writing to me, he responded to the charge that he sold out, by saying that both before and during his tenure in parliament he wrote to Heydar Aliyev, Azerbaijan’s president from 1993, and to Aliyev’s son and successor Ilham Aliyev, speaking out against human rights abuses and the systematic destruction of Armenian historical monuments in Nakhchivan.

The historian Jamil Hasanli, who later became one of the leaders of Azerbaijan’s opposition, was also a parliamentarian at this time. Hasanli remembers that during a break in sessions, he found Aylisli looking downcast. “‘Is something wrong?’ I asked him. Aylisli responded by saying, ‘You know, our government is dead, our parliament is dead, the intelligentsia is dead, we are also dead.’ I tried to cheer him up a bit and said: ‘But you are one of the most alive people in the country.’ He laughed and said: 'I’m also dead, I just died quite recently.’”

All this time, Aylisli was secretly working on the novella ‘Stone Dreams’. And in 2012 a new scandal erupted, triggering Aylisli into action.

At a NATO training course in Budapest in 2004, a young Azerbaijani officer, Ramil Safarov, brutally murdered an Armenian classmate, Gurgen Margaryan, and was given a long jail sentence. But in a deal between Hungary and Azerbaijan, Safarov was returned to his homeland eight years later, in 2012, only to be pardoned, set free and lauded by much of the Azerbaijani establishment as a “hero”.

As international criticism rained down on Azerbaijan for this grotesque act, Aylisli evidently decided his dissenting voice needed to be heard. He sent Stone Dreams for publication in Moscow at the end of 2012.

A dissenting protagonist

The novella is set in the year 1989, as Armenian-Azerbaijani violence escalates. The main protagonist, an actor named Sadai Sadygly, comes, like Aylisli, from the village of Aylis; unlike him, however, the character intervenes with more than words to counter violence. After being beaten by a mob for defending an Armenian, he is admitted to hospital in a coma. In flashbacks we learn how Sadygly was obsessed with the 1919 massacre of Armenians in Aylis and eventually decided to become a Christian as expiation. His sceptical wife rebukes him for forgetting the suffering of his fellow Azerbaijanis.

In Azerbaijan, the publication of the novella – or reports of it, as few actually read the Russian text – came like an explosion. Aylisli was vilified as a traitor by everyone from the president downwards and stripped of his state literary awards and special pension.

“He was not a fighter before, but suddenly he performed this brave deed,” said Shura Burtin. It seems he felt he must finally dissent from the path his country had taken.

The author says he is proud that Stone Dreams caused a stir, but also that his text was misunderstood. Sadygly, he says, is a “highly vulnerable person of high morals, who is on the edge of psychological collapse.” In the text itself, the author compares him to Don Quixote, the arch-defier of reality.

Decried and celebrated

Damned in Azerbaijan, ‘Stone Dreams’ was celebrated in Armenia – and also misunderstood, some say. Armenian writer and journalist Mark Grigorian said that much of the Armenian public – few of whom also read the actual text – merely concluded that an Azerbaijani writer had apologised to them, proving the Armenian cause was just.

“I think Stone Dreams is more about the hero’s conversation with God,” Grigorian said, who reads it as a deeper reflection by the writer on why evil has befallen his region.

Aylislis’s bold call was to put Armenian-Azerbaijani symbiosis at a higher level than the nation-building project of either country. The call was heard, but mostly unanswered. “The book is directed to [Armenian] intellectuals, I believe the intellectuals understood the message – this book shouts that it needs someone, a writer from the Armenian side, to respond,” Grigorian remarks. Some of them did respond, he says, but Armenia lacks an author with the same combination of literary talent and the status of “conscience of the nation”. (The writer who came closest to fitting that description was actually a contemporary and friend of Aylisli, Hrant Matevosian, but he died in 2002.)

Aylisli says that he has no desire to exculpate Armenians for their actions in the conflict. “They acted criminally and stupidly when they seized seven whole regions around Nagorno-Karabakh,” he wrote to me. “And it cost them dearly.”

Having found a new voice, Aylisli had more in store. He wrote a novella, entitled ‘A Fantastical Traffic Jam’, a straight-out political satire, with little of the pastoral lyricism of his other works. Its protagonist, a grasping official named Elbey, falls out of favour with the all-powerful “Master,” the leader of a post-Soviet republic named Allahabad and loses everything.

‘A Fantastic Traffic Jam’ was published in a small edition of just 50 copies, to test his friends’ reaction –- one copy of which duly fell into the hands of the all-seeing authorities.

Several commentators have speculated that this book was actually a graver sin in the eyes of the Azerbaijani leadership than ‘Stone Dreams’. In it Aylisli lifts the lid on the corruption and craven behavior in the inner circles of an authoritarian regime.

He spares no one. For example, he writes of a state-sponsored singer in the book, “it was impossible to doubt his love for the Glorious Allahabad Party, love that had cost at least fifteen thousand dollars.” This is the sum, we are told, that the singer receives in cash in a sealed envelope every time he sings songs glorifying the leader.

Reclaiming memory

The new Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict has left Aylisli more isolated, even as the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict remains unresolved and an alternative voice like his has never been needed more .

But Aylisli has no illusions as to why the authorities are keeping him so isolated. He says they are waiting for him to die. “For a long time I have had no doubts that they have a pre-agreed plan to keep me in this situation to the end of my life,” he wrote to me.

A banned author, whose books were burned, Aylisli risks being forgotten. PEN International has campaigned for him, but he remains a writer in a country few people know, who does not speak English and does not seek out publicity. Yet there is an appetite to read and hear him.

An online event organised by the Harriman Institute of Columbia University last December attracted hundreds of participants, many from the younger generation thirsting to hear someone who had so radically broken with the dogmas of nationalism surrounding the conflict. Yet Aylisli, a self-confessed technophobe, admits that his arm was twisted to appear live. He answered questions fluently for an hour, but seemed relieved to take a cigarette break when moderators gathered questions.

In Azerbaijan, few have backed him publicly. Aylisli told me that he has received messages of support – mainly from older Russian liberal writers, naming, amongst others, Boris Akunin, Andrei Bitov and Viktor Yerofeyev.

Katherine Young, his translator, enthuses about Aylisli’s early work and wants to see it published in English. What is for sure is that the more non-Russian speakers get to read his books – and to grasp that he is not just a civic activist, but a remarkable writer with a 50-year track-record – the more readers and supporters he will receive.

To hear Aylisli talk, it’s as though conflict has cast an evil spell over the Caucasus and struck its inhabitants dumb.

“We had so much that it was good when we were together. But for some reason everyone has decided to keep silent about that. It’s as though some kind of mysterious catastrophe occurred: people’s memory vanished in a flash. But it is memory that moves us forward in all our actions. But now it’s as though everyone has decided to live without memory,” he told those willing to listen.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.