7 ways policymakers should respond to the cost of living crisis

To win an economy that works for people and planet, we need a new approach to inflation

Headline inflation figures don’t tell us which prices are changing, in what direction, by how much, for what reasons, or to what effect | British Retail Photography / Alamy Stock Photo

David Barmes-1 February 2022

The UK’s cost of living crisis is taking its toll, particularly on low-income households. The anticipated change in the energy price cap in April is set to plunge an additional four million families into ‘fuel stress’, where 10% or more of their income is spent on energy. As the latest headline inflation figure hits 4.8%, the Bank of England is set to continue raising its base interest rate, increasing the cost of borrowing in an effort to exert downward pressure on prices by reducing demand for goods and services. But this will fail to address current sources of inflation, and could even exacerbate the cost of living crisis by lowering future output and employment. A search for alternative solutions is generating much-needed debate about how we should think about, measure and navigate price changes.

As we lurch from one crisis to the next, misguided monetarist views that treat inflation as the result of excess demand driven by growth in the money supply are more dangerous than ever. Prescribing higher interest rates and lower government spending threatens the prospects for achieving a sustainable and socially just future. Senator Joe Manchin’s use of rising inflation to justify quashing Joe Biden’s ‘Build Back Better’ bill – intended to tackle climate change, create jobs, and improve welfare and social services – is a case in point. If fallacious arguments about prices are left unchallenged, they will contribute to an inadequate response to the cost of living crunch, and continue to undermine much-needed efforts to invest in social safety nets and green infrastructure.

So as inflation rears its head, how should we respond? There are seven key points that should underpin new approaches to thinking about and managing price hikes.

1) Headline inflation figures don’t tell us much about the economy

The Office for National Statistics’ (ONS) headline inflation figure – the Consumer Price Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs (CPIH) – is a weighted average of price changes across a ‘representative’ basket of approximately 700 goods and services. Tracking and presenting price changes of these items is a vital job, which ONS statisticians carry out laudably, but headline inflation figures alone don’t tell us specifically which prices are changing, in what direction, by how much, for what reasons, or to what effect.

This is important because prices don’t move up and down in perfect synchrony, but rather tend to vary wildly across sectors. For example, in the early stages of COVID-19, prices plunged for many recreational activities, package holidays and meals out, but skyrocketed for pandemic-related essentials such as masks, rubber gloves, disinfectants and many food items. In addition to sectoral variations, prices also move in divergent ways within sectors and even within specific categories of goods and services, often in ways that even the ONS’ vast dataset of 700 items does not capture. A rather jarring example of such a variation: funeral service prices on average decreased in 2021, but the price of cremations without a service – the cheapest type of funeral – rose by 6%.

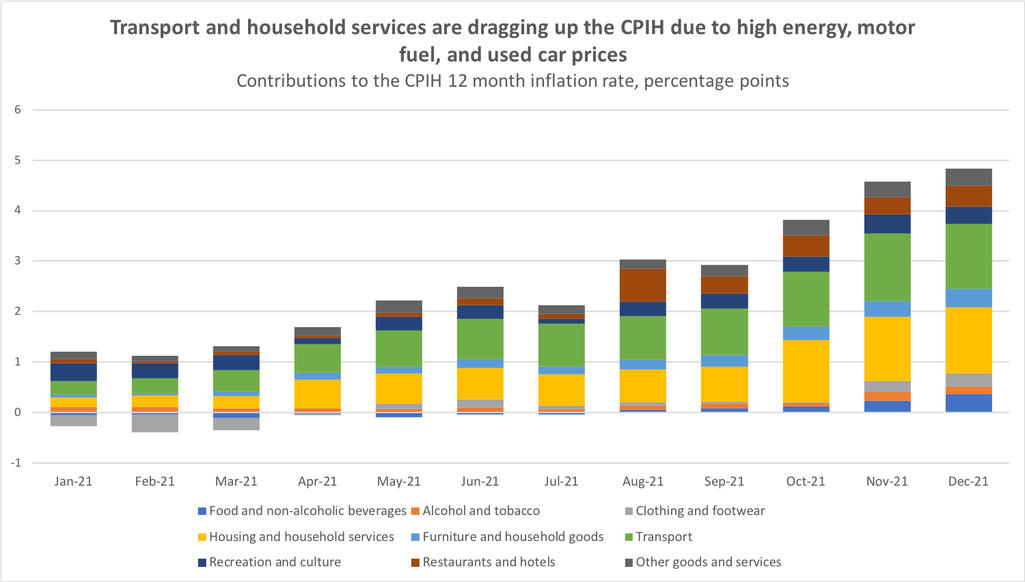

Due to these divergent changes, big price changes in individual sectors or categories of goods can significantly pull the headline inflation figure in one direction or another. For example, in August 2021, used cars and the end of the UK government’s ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ scheme the previous year accounted for a sixth of the 3% CPIH figure. Although price rises have become slightly more broad-based recently, a full third of December’s 4.8% CPIH figure came down to motor fuels, used cars and household energy.

Even if all goods and services were displaying similar price increases, making the index more reflective of a ‘general’ rise in prices, one would still have to look beneath the headline inflation rate to grasp that dynamic.

Ultimately, CPIH inflation is just one inflation rate, based on questionable concepts of a ‘representative’ basket of goods, a ‘typical’ spending pattern, and an ‘average’ household. In practice, there are as many different inflation rates as there are patterns of consumption. The idea of one true inflation rate for the whole population is not all that meaningful or useful for informing policy. To understand how price changes are affecting different households and what an effective policy response might look like, it’s necessary to look beneath and beyond existing headline inflation figures, as the ONS itself recently acknowledged.

2) Increases in the prices of essential goods and services hit the poorest the hardest

While the distributional consequences of price increases can be complex and varied, one constant is that low-income households are far less able to absorb increases in the prices of essentials, such as energy and cheap food items. This should be obvious, but multiple economics journalists seem to be missing this basic point, claiming that “higher earners will be worst hit by rocketing inflation” and that the story of recent inflation is “one of shared pain rather than concentrated pain among the poorest”. In reality, there’s no doubt that those struggling to pay rent and put food on the table are feeling the surge in energy bills and cheap food items far more acutely than wealthy households.

Furthermore, essential items that make up the vast majority of poorer households’ budgets are highly ‘inelastic’, meaning that their consumption cannot be easily substituted or deferred to a later date. Simply put, people need to eat, stay housed, and use energy and water on a daily basis. On the other hand, the purchase of non-essential items, which feature to a greater extent in wealthier households’ consumption baskets, can be more easily substituted or deferred. Buying cheaper wine, staying in for dinner instead of eating out, or delaying the purchase of the latest iPhone may be irritating and inconvenient to some consumers, but it won’t put their lives at risk or threaten their basic human dignity.

3) Price changes are driven by many economic and political factors

Even central bankers, whose main job is to target a given inflation rate (usually 2%), are starting to admit that they have no reliable theory of how ‘inflation’ works. Attempts to develop simple models of inflation have papered over the fact that companies’ price-setting behaviour is affected by a wide range of factors often entirely unrelated to the money supply, such as exploitative pricing by companies, supply chain disruptions, and geopolitical tensions.

Looking into the key items pushing up recent CPIH figures offers a good example of how myriad economic and political factors feed into price changes. Energy price pressures since late 2021 have resulted from Britain’s reliance on depleted European gas stocks, high demand for liquefied natural gas in Asia and Latin America, and a drop in gas supplies from Russia. Heightening tensions between Ukraine and Russia could exacerbate this situation. Meanwhile the price surge in second-hand cars, another significant contributor to CPIH inflation, has largely been caused by a shortage in microchips preventing the production of new cars earlier in the pandemic, meaning there are fewer second-hand cars on the market today. Other drivers of recent price rises include COVID and Brexit-related worker shortages, disruptions in the global shipping network resulting from the shuttering of factories followed by changes in patterns of consumption, and corporate profiteering as the likes of BP and Shell have grown their profit margins while ordinary families struggle to pay their energy bills.

Monetarist views that focus on high government spending and loose monetary policy as drivers of inflation ignore all of these far more important supply-side dynamics. This failing results in regressive policy outcomes that aim to reduce consumer demand by increasing unemployment and making people poorer. Understanding what forces are driving particular price changes is a necessary prerequisite for designing an effective policy response that minimises, and protects the most vulnerable from, increases in the cost of living.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.