‘I was forcibly evacuated from Mariupol to Russia’

A Ukrainian writer was forcibly evacuated from the besieged city of Mariupol into Russia. This is her account of what happened

AUkrainian translator and editor has told of her deportation to Russia from the besieged city of Mariupol.

Natalia Yavorska’s* first-person account gives substance to the claim made by city authorities that Russian forces had been taking people across the border.

She says refugees are being questioned in makeshift camps as they are ferried into Russian territory. Some, like Yavorska herself, are able to leave once this is done. Others with nowhere to go have little choice but to take low-waged work at local shops.

Originally published in Ukrainian by the news website Graty, the report was verified by contacting volunteers working with Ukrainian refugees in the Russian city of Taganrog, who initially stated that refugees had been brought to the town in groups, but did not say whether they had come under duress – and subsequently stopped responding to requests.

Below is an abridged English translation of Natalia’s account, beginning with her time in a bomb shelter in a village just outside Mariupol. The original is here.

Shelter

They started shelling the building we were in on 8 March. It was so completely destroyed that we actually calmed down a bit – there just wasn’t anything left to bomb, only our basement remained. But for some reason they bombed it again on 10 March, probably to make it collapse on us.

By 15 March, the Russian military had occupied most of our village. They came to our shelter while going from house to house, and said that everyone needed to leave – they were evacuating the women and children. We asked if we could stay and they said: “No, you can’t,” like they were giving an order. We had nowhere else to go except the shelter. Several men with large families managed to leave the village, but we had no means to do so.

It was the first time I had been outside since arriving at the shelter. It is a wild feeling to come out and see that the building you were in is not there any more – it’s just a pile of bricks. There were a bunch of fallen trees and towers – whole parts of the city collapsed. It’s a surreal feeling, seeing that my old school cafeteria is now a bunch of bricks, and textbooks are strewn all over. There was still a display on a wall, the school’s honour roll, with a picture of my sister, and all around us were Russian soldiers. [Editor’s note: this was based on their uniforms and the language they were speaking.]

At first, we were told to go to a bombed-out school they were occupying, and then took us on foot to the road out of town.

Our group contained about 90 people; there had been 2,000 in the village. After leaving the bombed-out school, they transported us around by bus several times.

This was a forced evacuation: none of us wanted to leave Ukraine. If we had had a choice, we would have stayed, or gone further into Ukraine. Some said they wanted to stay, but the Russians said we couldn’t, in a tone that left no room for argument.

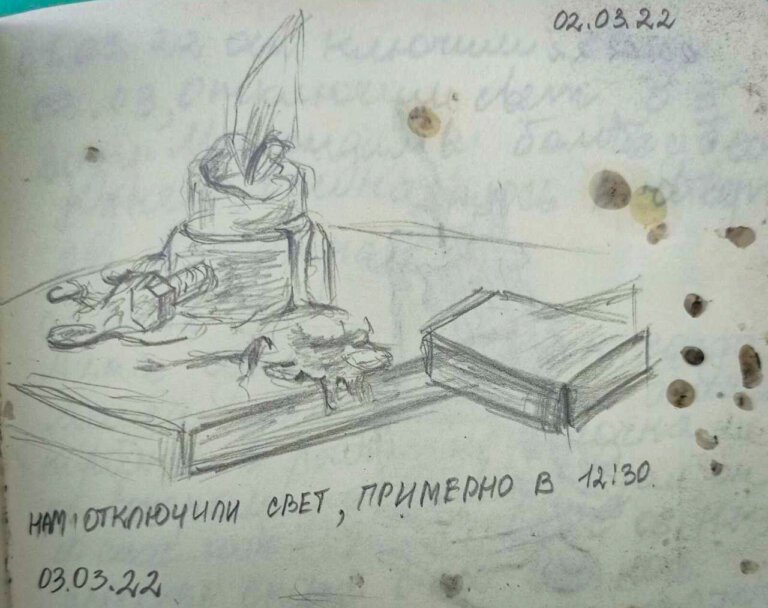

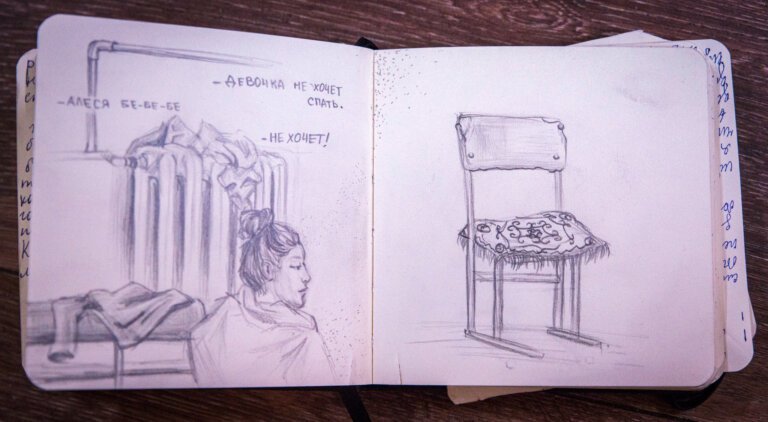

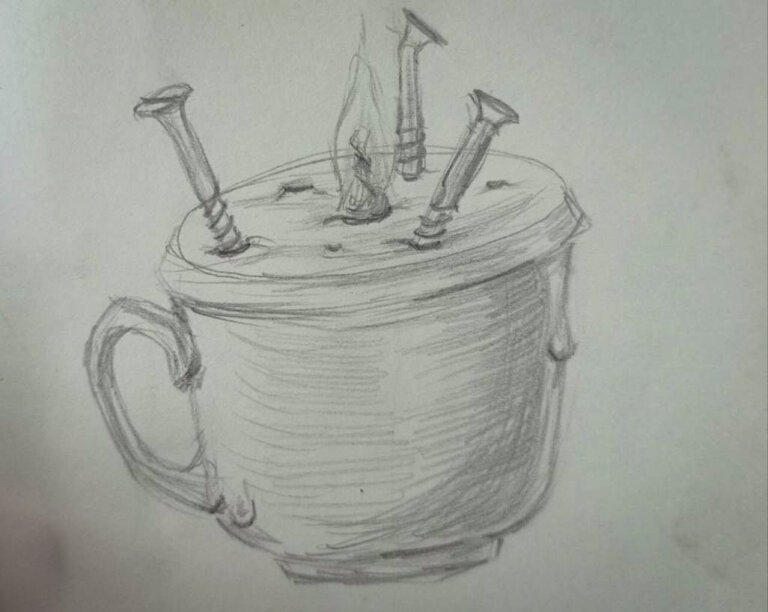

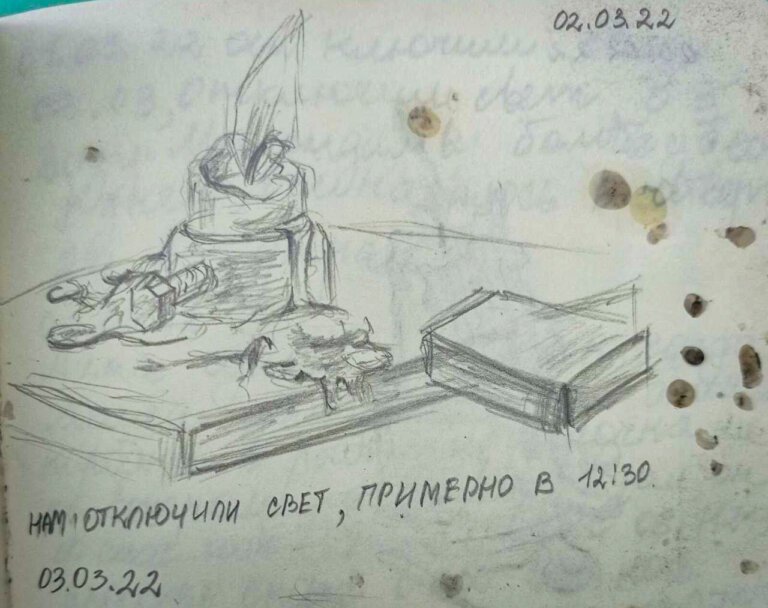

Sketch from a diary by a woman inside the bomb shelter

The shelter was basically the only place we had left. Most of the people with us no longer had houses, and there was nowhere for them to hide in the village.

On the road out of the village towards the Donetsk highway, they put us in military trucks. We were taken to the nearest village [editor’s note: we have chosen not to name this village so as not to identify the author], which had been captured a few weeks prior. Fighting had stopped there because the Ukrainian soldiers were gone. They put us in a school in that village for a day. The next day we were loaded onto buses.

Everyone, for the most part, treated us like criminals or convicts on their way to prison. We didn’t even have the right to know where we were being taken. They didn’t tell us until the very end. If you asked: “Where are you taking us?”, they answered: “To somewhere warm.” They expected us to be grateful that we had been freed from our homes.

Of all my possessions, all I had left was the sweatshirt I was wearing and a few photographs. Others had no photos, no videos, nothing.

The buses were taking us to Novoazovsk [a Ukrainian town under the control of the so-called “Donetsk People’s Republic” since 2014], but we only learned that later. It took a long time; the driver knew where we were going, but each time they arrived somewhere along the way they were told the roads were bombed out and would have to take a diversion. There was a complete lack of coordination. Everyone on the road treats you like a sack of potatoes. They had been ordered not to give us any information.

In Novoazovsk, there were so-called filtration camps. I didn’t make this up – that’s how the Russian forces refer to them. There were workers in the uniform of the Russian Ministry of Emergencies and Disaster Relief at the camps. We were able to connect to the wi-fi intended for the Russians – they had bombed the communication towers and cut off all signals, but had left the wi-fi’s password as 12345678. All we did was try a few different passwords and bam, we had internet. That’s when I first learned that the centre of Mariupol was being bombed, and it was a big shock. The Russian soldiers told us they had already captured Kyiv and Kharkiv.

My understanding is that Novoazovsk is a transfer point. It was pretty grim, because there were a lot of military vehicles with images of [Chechen leader Ramzan] Kadyrov, a lot of Chechen soldiers, and military equipment being redeployed. When Russian truck-mounted rocket launchers pass you by, it’s eerie. At the same time, everyone is trying to pretend everything is normal: there’s the Russian Ministry of Emergencies and Disaster Relief, buses, tents, pills, they even take your blood pressure. The Chechens gave us some sausage. It was just crazy.

Filtration camp

A filtration camp is a tent where a bunch of soldiers are set up. We all sat on the buses, taking turns going in. First they photograph you from all sides, apparently for the facial recognition systems now being rolled out in the Russian Federation. Then they fingerprint you and scan your palms. Then they interrogate you before they decide to release you or not.

They ask which of your relatives stayed behind in Ukraine, whether you’ve seen Ukrainian troop movements, what you think about Ukrainian politics, the Ukrainian authorities, and “Right Sector” [a Ukrainian far-right movement]. They have a large questionnaire they go through, but the questioning wasn’t harsh. Then I had to give them my phone. They connected it to a computer for 20 minutes and I saw them download my contact list, but I don’t know what else they were doing. They may have been copying the IMEI data used to identify my phone.

Sketch from a diary by a woman inside the bomb shelter

We waited four or five hours to finish the filtration camp. Then we waited another few hours. There were no toilets on the buses where we were waiting to be questioned. There was one in a trench far away but my grandmother, who is 70, had twisted her leg and couldn’t walk normally.

Then they took us to the border of the “DNR” and Russia. We spent all night on the bus in really harsh conditions.

My time in the Russian Federation began with a physical search. Men and women are interrogated on a selective basis. The majority of those being questioned were men, but I was one of the unlucky women who landed on the list.

You sit in a basement for two weeks being shelled, and the first person you meet on the outside is a Russian FSB officer. He got me really paranoid. I have written some works of fiction about Ukraine, about the war – I don’t think they're super notable. But I still felt paranoid. I was scared – he kept asking me whether I knew about Ukrainian troop movements, what I knew about Ukrainian soldiers and so on. He’d ask one question, make a joke about something, then ask the same question to see if I had been lying or not. But really we spent most of the time talking about my partner in St Petersburg; what disturbed the FSB officer the most was the fact my partner is older than me.

I’m registered on all the social networks with a Ukrainian phone number. When they asked, I told them the wrong phone number on purpose, but even that still felt risky. They wrote down my phone numbers and asked a lot of questions, saying I was “too mysterious”. It feels like the worst thing you can hear is when an FSB officer leads you away is that you’re “too mysterious”. My heart sank at the sound.

But we were released from questioning. We tried to leave the camp with our family – my grandmother, mum, brother, aunt and cousins – but we weren’t allowed to.

Sketch from a diary by a woman inside the bomb shelter

Escape

Instead, we were forced to go by bus to Taganrog. They told us we’d then go on to Vladimir [a city in central Russia] by train.

But instead, when we reached Taganrog, we made the choice to go to Rostov, where we spent the night at my aunt’s grandmother’s.

It’s crazy there. They’re very hospitable, but they’ve been completely brainwashed by Russian propaganda. They say: “Don’t worry – you’ll go back to Mariupol by autumn, everything will be cleaned up there, and it will all be fine.”

When we were on the Rostov-to-Moscow train, it was such a strange feeling to hear everyone discussing Mariupol. People on the train were claiming that, in Mariupol, biological weapons were being developed [by the West] to destroy the reproductive systems of Russian women. It felt like a kind of collective dream. Before the war, I really had believed that Russians were not the same as Putin. I was sure that no one wanted war with Ukraine. Now I think that even sensible people in Russian society are a part of this and are also responsible for it.

I’ve been calling friends who had no means to leave the refugee camps [in Russia, where they were taken after the filtration camps]. They were given Russian SIM cards. We want to help them all leave somehow. They're fed there, given lodging, but they don’t have tickets to go anywhere. They work as cashiers and other personnel at nearby local supermarkets. People are basically working for free. I think they’re only being brought out of Ukraine for propaganda purposes, to show that Russia is evacuating people.

Sketch from a diary by a woman inside the bomb shelter

In Vladimir, I have been told, people’s living conditions vary; some are lucky, some are not. They get a one-time state payment of 10,000 roubles (£73), but some don’t even get that. If women and children are given temporary asylum rather than refugee status, they are able to leave at any time. But the situation with men is less clear: Ukrainian men may not be allowed to leave the Russian Federation.

Everyone I talk to is severely exhausted. All of them have started having health problems. A lot of the old women have mental health issues, and getting them out of Russia isn’t straightforward. They no longer have homes in Mariupol, and just the idea of setting off somewhere else is very difficult.

But it’s even harder to live in a place that completely denies your experience. It’s scary when you come across this in Russia: you know the truth about what happened, but everyone else is stuck in a dream, and you have to guess what this dream is about.

You can only stay in Russia for 15 days without official registration, so you have to manage to leave during this time. People who didn’t have any money, for example, ran into problems. Their relatives in Russia wanted to chip in, but they have nowhere to send the money. A few of them find someone nearby, send them the money, and those people send the cash to the camp.

A few people in the camp didn’t have passports. When the shelling started, they didn’t have time to grab them, and had no chance to go back home subsequently. They are given Russian certificates allowing them to work, but the question of how to leave the country remains. The only option is to apply for repatriation, but it’s unclear how to do this because the Ukrainian consulate isn’t open.

We went to Moscow from Rostov, and then on to St Petersburg. We were there for three days. On 22 March, we set off for the border. We prepped well and wiped our phones. But oddly enough, it was pretty easy to leave – there was just a formal interrogation about your relatives. For some reason they again asked for the phone’s IMEI.

My grandfather stayed behind in the village near Mariupol. My grandmother regrets having left. She wanted to stay with him but everything happened so quickly and haphazardly that she couldn’t make a decision. Her son also stayed behind. I am worried he’ll be quickly issued a “DNR” passport and forced to fight.

My grandparents, who cooked for us, also remained there. We even managed to send someone to pick them up and evacuate them, but they refused to go. They feel this is their land. All the houses around my grandfather’s are destroyed. He stayed in a home with shattered windows because he believes that place is his and no one has the right to get in the way of that.

They’ve started getting phone signal again. My grandfather says there is severe looting in the villages, and that the Russian soldiers are getting drunk and shooting through the ceilings of the houses.

There are a lot of women in the shelter with children. While the shells are falling, they’re running around from destroyed house to destroyed house, looking for something to eat. But the Russian soldiers are occupying the buildings. It’s a terrible situation, but it’s different from what I experienced and I don’t know anything about it.

%20(2)%20(2)%20(1).png)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.