To crush climate action, fossil fuel advocates are copying anti-BDS laws

US conservatives are banning boycotts of oil and gas companies, using anti-BDS legislation as a model. Experts warn the tactic will spread even further.

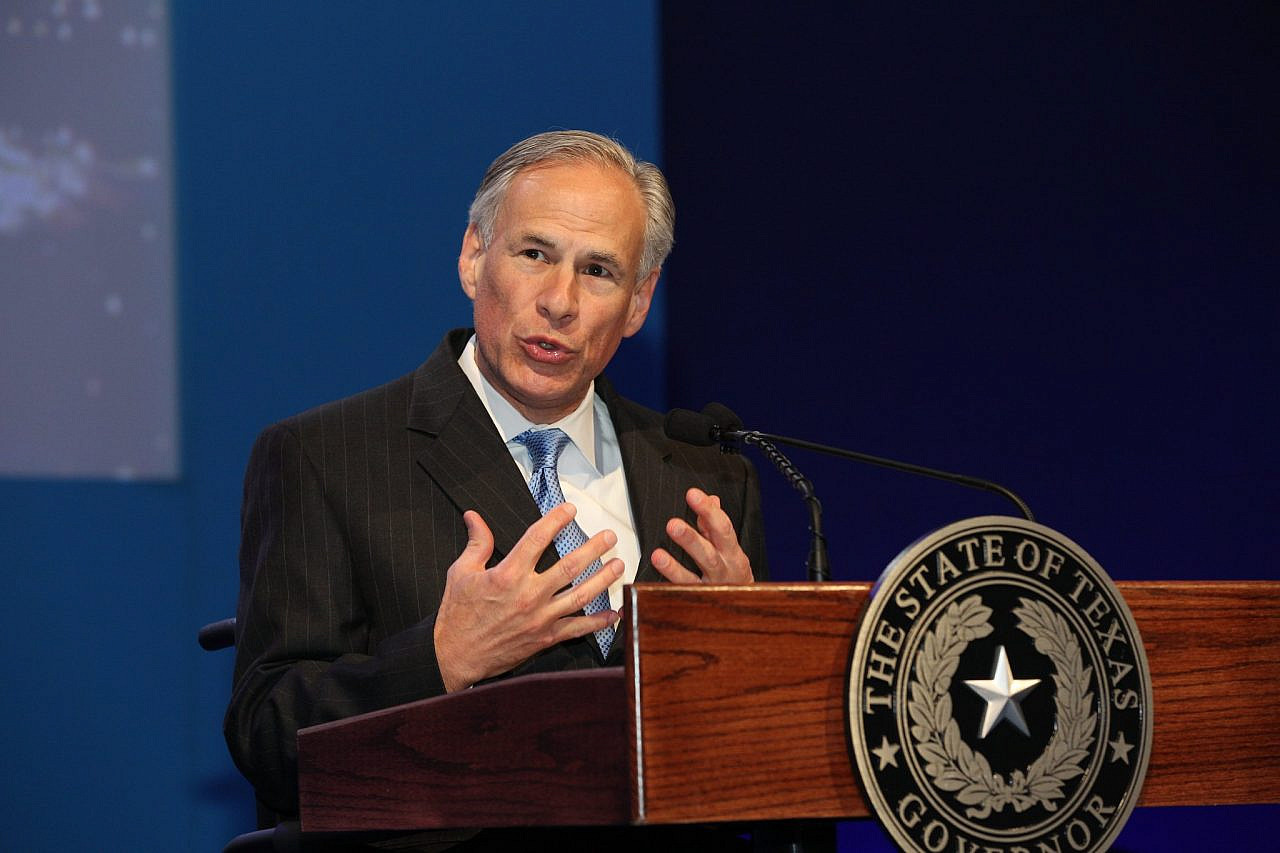

Last summer, Texas Governor Greg Abbott signed into law a bill designed to protect the oil and gas industry that has enriched so much of the state’s ruling class. SB13, which went into effect on Sept. 1 last year, prohibits Texas from investing in or granting contracts to any entities that boycott energy companies.

State Rep. Phil King, who championed the bill in the state legislature, was buoyant. In a column for the conservative Texas Public Policy Foundation, he welcomed the new legislation’s unmistakable message: “If you boycott Texas energy, Texas will boycott you.”

King also made it very clear where he and his colleagues had drawn their inspiration for the new legislation.

“In 2017, I championed similar legislation regarding Israel,” King wrote. “Thanks to Gov. Greg Abbott and the Texas Legislature’s decisive action, the state of Texas no longer contracts with companies that boycott Israel. We’re proud to stand firmly with one of our greatest allies — and to show the same support to the energy workers who power our state and our entire nation.”

For policy analysts and activists who watched as legislation criminalizing support for the non-violent, Palestinian-led Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement moved steadily through state legislatures across the country in the preceding years, the idea that states would use it to ban political expression on other, unrelated topics came as no surprise.

Since 2016, 31 states passed laws or enacted executive orders voicing their opposition to the BDS movement and, in many cases, dictating that states boycott companies that support it.

The anti-BDS movement is ongoing. In the last year or so, however, legislators in Republican-controlled states have adapted laws criminalizing support for the BDS movement to criminalize all manner of other things conservative interests oppose.

Both Texas and North Dakota, for example, have new laws prohibiting their states from investing in companies that support divestment from either the oil or gas industries, while Texas also has a law prohibiting investment in companies that support divestment from the firearm and ammunition industry. Similar legislation is pending in a further 14 states. Four states, Arizona, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Wisconsin, have drafted legislation that would make it illegal for the state to do business with companies that require their employees to receive COVID-19 vaccines.

“It works on everything,” Lara Friedman, president of the Foundation for Middle East Peace, said of the anti-BDS template. “If your logic is that the state has a right to deny contracts to people merely based on their refusal to give up their right to free speech on a given issue, you can apply that to anything. So it’s a matter of creativity here.”

An early warning ignored

Republican legislators have not mounted their battle against boycotts alone. At its national summit in San Diego last December, the Energy, Environment, and Agriculture Task Force of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) voted unanimously to back two new pieces of model legislation directing states to blacklist companies supposedly boycotting the oil and gas industry. This proposal forms part of an effort to activate Republican voters around “critical energy theory,” in the same way many Republicans believe voters in Virginia were activated by attacks on “critical race theory” last winter.

In an email obtained by reporter Alex Kotch in December, Jason Isaac of the Texas Public Policy Fund wrote to ALEC members that the proposed legislation “is based on anti-BDS legislation supported by ALEC regarding Israel and was recently passed in Texas to include discrimination against fossil fuels.”

What ALEC supports matters a great deal. The Republican-aligned nonprofit, comprised of state legislators and corporate representatives and funded in large part by the Koch brothers’ empire, holds immense sway in what legislation is introduced in states across the country. Three states have already introduced a version of their Energy Discrimination Elimination Act designed to protect the fossil fuel industry from divestment, and more have indicated their support.

ALEC’s position means that the anti-BDS template will likely continue to be used as a cudgel against socially-conscious companies in the coming months. The frustration for a number of experts is that when ALEC was originally disseminating anti-BDS measures all over the country in years past, relatively few liberals and progressives sounded the alarm.

Friedman said that when she was meeting with legislators on Capitol Hill during Barack Obama’s presidency, when almost nothing enjoyed bipartisan support, ironclad backing for Israel remained a point of agreement.

That has not changed in recent years, even as a select number of progressives who have been outspoken in their support of Palestinian rights have joined Congress. In 2019, the Democratic-run House of Representatives voted 398-17 for legislation opposing the BDS movement. Last fall, the House voted 420-9 to send $1 billion in supplemental military assistance to Israel, despite Senate Appropriations Chairman Patrick Leahy of Vermont telling reporters that “The Israelis haven’t even taken the money that we’ve already appropriated.”

Friedman criticized Democrats for their strategic shortsightedness on issues of free speech and Israel.

“On this BDS legislation, you see progressives lining up with the most hardline right-wing forces in their state, and never once looking in the mirror and thinking, ‘Huh, I wonder if the fact that they’re in favor of this should make me think twice about what it is?’” she said. “And the answer is, ‘No, we’re not going to do that. In this one case, they’re on the right side, and we can agree.’”

But that bipartisan support to limit free speech on Israel provided a template that conservative forces have seized on to ban free speech on other issues without any support from Democrats — illustrating again the danger of treating matters related to Israel as disconnected from everything else.

“If one group is not free, then no one is free,” Kotch said. “So when Democrats, probably for a combination of ignorance and political pressure and whatever else, support banning free speech when it comes to criticizing the Israeli government, it’s going to come back to bite them when other people use it for other purposes. You should never be banning free speech.”

Defending the indefensible

That legislation banning divestment efforts in the oil and gas industry is being drafted now is no coincidence. With the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warning last summer that the world must act decisively in the coming decades to limit the devastating effects of global warming, the long-term future of the industry is economically uncertain and, for many, morally indefensible.

“It’s a response to calls for divestment,” Kotch said of the ALEC push. “Most of these banks and stuff that are supposedly targeted by these laws haven’t done anything meaningful to divest from fossil fuels, but the threat is there.”

According to Friedman, there is a similar logic at work in the current extremity of conditions in Israel and Palestine.

“The reason there is this energy to boycott BDS is that, as Israel has moved away from any pretense of support for a two-state solution, the policies are impossible to defend,” Friedman said. “And if the policies are impossible to defend and the actions are impossible to defend, the only defense is to shut down the critics.”

In many ways, this is new ground for organizations like ALEC, which for years existed primarily to champion free market ideology. In recent times, however, both ALEC and the Republican Party at large have increasingly strayed from economic doctrine to take up a range of sociocultural fights.

“Particularly after Trump was elected, [ALEC] moved very significantly to embrace the Christian right,” David Armiak, research director at the Center for Media and Democracy, said. “It’s very much tied to a white nationalist direction.”

Part of that shift is political: ALEC’s dues-paying members need Republicans in elected office, and Republican voters, as evidenced by Trump’s enduring popularity, are motivated by cultural issues. ALEC and its allies have also been mobilized by the threat of corporations boycotting states that pass anti-transgender or flagrant voter suppression bills, as well as corporations signaling their support for the Black Lives Matter movement.

Much of ALEC’s recent messaging, then, targets what it calls “woke capitalism.” In that December email, for instance, Isaac framed ALEC’s efforts to protect the oil and gas industry as an “opportunity to push back against woke financial institutions that are colluding against American energy producers” in “politically motivated and discriminatory investing practices.”

As ALEC has grown closer to the evangelical right and the white nationalist movement, it has grown closer to Israel as well. Armiak said that in recent years, Israeli lobbyists have attended and presented at ALEC meetings, run booths at ALEC events, and participated in ALEC panels on Israel-related topics. In 2018, ALEC organized an all-expenses-paid trip to Israel for a group of friendly Texas lawmakers — a reflection of shared economic, political, and ideological interests between the Israel lobby and the American right.

Trench lawfare

The laws discriminating against companies on the basis of peaceful political expression have, predictably, been challenged on constitutional grounds. The Eighth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals struck down Arkansas’ anti-BDS law last year, and earlier this year, a U.S. District Court ruled that Texas could not enforce its anti-BDS law against a Palestinian-owned Houston engineering firm because it violated the firm’s free speech rights.

Nevertheless, states are working to craft bills that are more difficult to challenge in court. After small companies challenged the constitutionality of a number of anti-BDS laws, Texas and other states started amending those existing laws and writing new ones that apply only to larger companies or contracts with the state of $100,000 or more — banking on the notion that larger companies won’t want to risk the reputational harm of major lawsuits to keep the law within constitutional boundaries.

ALEC itself is well aware of the constitutional challenges it faces. In that December email, Isaac wrote that the language of the fossil fuel boycott bill “has also been carefully crafted to uphold First Amendment free speech principles and avoid restricting companies’ ability to adopt political stances on energy.”

Friedman suggested that one of the cases challenging the legality of the boycott laws may eventually make its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, and that both opponents and proponents of the law “feel like they have to play this out.” In the meantime, however, the chilling effect on free speech will likely continue.

“It seemed to me that it was inevitable that [the anti-BDS laws] would be repurposed this way,” Friedman said of the slate of new laws. “It seems improbable that it’s going to stop at these things.”

%20(2)%20(1)%20(1).jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.