How an army refusal letter became the last stand of the Zionist left

Two decades ago, hundreds of Israeli reservists caused a national sensation for refusing to serve in the occupied territories. But what remains of their legacy?

We, reserve combat officers and soldiers of the Israel Defense Forces, who were raised upon the principles of Zionism, self-sacrifice and giving to the people of Israel and to the State of Israel, who have always served in the front lines, and who were the first to carry out any mission in order to protect the State of Israel and strengthen it.

We, combat officers and soldiers who have served the State of Israel for long weeks every year, in spite of the dear cost to our personal lives, have been on reserve duty in the Occupied Territories, and were issued commands and directives that had nothing to do with the security of our country, and that had the sole purpose of perpetuating our control over the Palestinian people.

[…]

We hereby declare that we shall not continue to fight this War of the Settlements.

We shall not continue to fight beyond the 1967 borders in order to dominate, expel, starve and humiliate an entire people.

[The Combatants’ Letter, January 2002]

In 1985, the enigmatic and much-admired orthodox Jewish polymath Yeshayahu Leibowitz, then a professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, gave an interview to the daily paper Yedioth Ahronoth, in which he expressed his wholehearted support for the army reservists who were refusing to serve in Israel’s ongoing war in Lebanon.

Refusal, Leibowitz argued, was a legitimate, even desired political tactic in the post-1967 Israeli reality. “Refusal to serve, even if it’s only the norm within a minority, might disable the national-fascist consensus, and become the first step on the road out from barbarism,” Lebowitz said. If 500 officers were to refuse to serve in the occupied territories, he predicted, the occupation would end.

In Israel, military service was and still is seen as an almost sacred duty, and Leibowitz’s interview was met with public uproar. Yet, as time went on, it was the Israeli left that became haunted by Leibowitz’s words. The number 500 received mythical status — the silver bullet that, with all other options exhausted, could fulfill the goal of ending Israel’s military rule over the Palestinians.

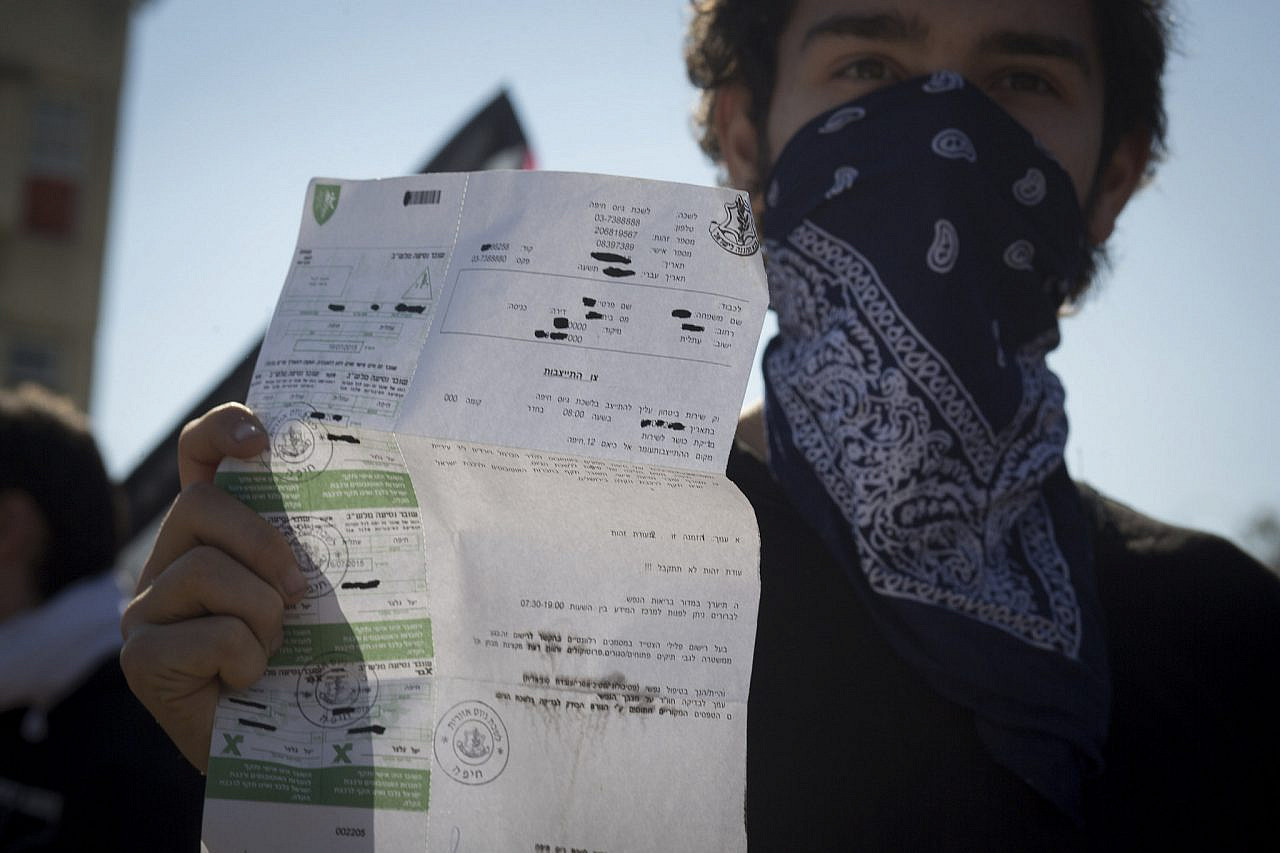

In January 2002, at the height of the Second Intifada, a group of 51 combat reservists published a letter in which they stated their refusal to serve in the occupied territories. The army’s presence there, they said, was no longer about protecting Israel, but instead was intended “to rule over, expel, starve, and humiliate a whole nation.” Dozens of others signed their names to the letter within weeks and, ultimately, close to a thousand soldiers and officers expressed their support for the movement. Many of them were discharged from their units; hundreds served prison terms, ranging between a week and a couple of months. It was a key moment in the history of the Israeli left, and the strongest act of opposition that it mounted during the Second Intifada.

The occupation didn’t end.

An immediate sensation

The 20th anniversary of what came to be known as “The Combatants’ Letter” went by almost unnoticed this past January. Some members of the group — who later organized themselves as “Courage to Refuse” — attempted to mount a nostalgic reunion, but preparations were put on hold due to the outbreak of the Omicron variant of Covid-19. The media, which debated the letter non-stop when it was published, has all but forgotten about it. Even on social media, I could not find more than a handful of posts mentioning one of the most significant political actions by the Israeli left in decades.

One exception was a long Facebook post by Courage to Refuse founder David Zonsheine, which harkened back to the early days of the movement, and went into the reasons that led him — a young officer in an elite special forces unit — to initiate “The Combatants’ Letter” along with fellow soldier Yaniv Iczkovits. The decision to publicly refuse military service changed his life, Zonsheine wrote. When he and Iczkovits penned the letter, a friend who had previously refused told them they would be lucky to get 10 people to co-sign it. Zonsheine agreed. But once Iczkovits started circulating the letter among his university friends, he found dozens who were willing to sign.

The first 51 names appeared, alongside their ranks and army units, in an ad published in Haaretz’s print edition. The publication of their letter caused an immediate sensation. This was already the second year of the Intifada; hundreds of Palestinians and Israelis had been killed, the Israeli left was in ruins, and public opposition to the occupation had reached a dead end. Suddenly, the letter presented a new idea, something serious and big that was worthy of the moment. More wanted to join, and what began as a few words on a page transformed into a movement.

Political leaders and army generals rushed to condemn the letter. The Knesset Committee for Foreign Affairs and Security held a lengthy debate on the initiative, in which the army’s then-Chief of Staff Shaul Mofaz accused the officers who initiated the letter of mutiny, warning that the army has ways to deal with soldiers who are determined to continue refusing.

Among the rank and file of the Israeli left, the refusal movement was all people talked about. The letter merged the political and the personal, and forced even those who opposed refusal to ask themselves how far they would be willing to go in their opposition to the occupation. By the time I signed the letter in April of that year, it had more than 200 names on it: paratroopers, tank commanders, lieutenants, and captains serving in field units — even submarine and patrol ship officers who refused to serve in the navy’s post in the Gaza Strip.

Along with the political attacks, the letter generated a lot of sympathy. “We got hit hard,” Zonsheine said when I spoke to him in early March, “but there was also something in our public position — we were photographed in uniform, with our ranks and berets — which made us familiar to the Israeli public. Years later, I met people from academia who told me, ‘We signed the professors’ petition supporting you, and we aren’t even on the left.’” Zonsheine attributes this to the letter’s boldness and clarity, against the backdrop of the confusion and despair of the Second Intifada wherein many felt that the Israeli left had lost its way.

Courage to Refuse limited its opposition to Israeli policy to the post-1967 occupation; this was both its strength and its weakness. Its logo was a Star of David and its members declared that they were “willing to continue to serve in other missions that would serve the security of the State of Israel.” Each signatory could decide for him or herself what constituted a “mission relating to the occupation.” Most simply chose not to serve beyond the Green Line in any form, as the letter suggested.

On the margins of the mainstream

Today, “The Combatants’ Letter” seems like a strange document. It promotes one of the most radical acts a Jewish Israeli can commit, while wrapping it in militaristic and Zionist language. The pathos, self-confidence, and privilege of the letter is so alien to the way the left speaks now, that it could make one cringe. It is impossible to imagine such a text being published, not to mention celebrated, today.

“Courage to Refuse initially succeeded because it knowingly obeyed the rules of the Israeli hegemony,” says Prof. Yagil Levy, whose research focuses on the Israeli military’s relationship with civil society. “It took a very subversive act — even Meretz opposed refusal — but it did it in a sort of conservative way, not speaking in the name of universal values but in the name of the status and [national] contribution of those who signed the letter. And it worked,” Levy continues. “After the letter went out, one poll showed 23 percent of Israelis were sympathetic toward refusal. At the height of the Intifada! Being on the margins of the mainstream — that was their secret. If they had been outsiders, the movement would have died before it was even born.”

Indeed, the activists in Courage to Refuse were as privileged and hegemonic as it gets, even 20 years ago. All the names on the initial letter, and an absolute majority of those who would come to sign it, were men. Most of them were Ashkenazi, and many hailed from elite units. Perhaps this is the reason even the left doesn’t like to remember the letter: it seems to confirm all the clichés and accusations leveled at it, and flies in the face of today’s values of gender and ethnic diversity.

Zonsheine doesn’t deny this fact. “Refusal is a privilege,” he wrote in his Facebook post. “It took years of learning to understand who is in the position to take part in such an act,” he told me. “I went to a great school in Ramat Hasharon [an affluent Tel Aviv suburb]. I work in hi-tech. We were never rich, my dad didn’t even finish high school, but I grew up with such a sense of comfort and ownership of this place… And for many, many people, it’s not this way.”

“My ability to refuse is a thousand times greater than that of a Mizrahi woman from Dimona [a city in the Negev/Naqab symbolic of Israel’s socioeconomic periphery],” Zonsheine wrote. “That doesn’t mean that there aren’t women from underprivileged backgrounds who refused, and I am deeply moved and admire their courage. Those who refuse are taking their privileges and using them to dismantle the most central privilege of Israeli Jews — to rule over the Palestinian people.”

A mixed legacy

Decades later, it is difficult to judge the success or even the impact of initiatives such as Courage to Refuse. Political reality is messy, and change never comes in a linear fashion. But in terms of the Israeli public debate, no other initiative on the Zionist left has had such an impact since then. This was its last stand — the Alamo of the Oslo generation, or at least its most radical contingent. The Jewish left has been looking for its voice in the Israeli conversation ever since.

Courage to Refuse had tangible impacts as well. In 2004, Dov Weissglas, one of then-Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s most intimate proxies and one of the masterminds behind Israel’s unilateral withdrawal from Gaza, told Haaretz’s Ari Shavit that the refusal movement was one of the reasons for the disengagement, which was carried out a year later.

“Courage to Refuse showed that a group of upper-middle class, secular Jews who were part of the core of the military can suddenly turn away from it,” Levy told me. “It was a groundbreaking event, and the army was deeply concerned by it. 2002 saw a rise in internal criticism of [Israel’s policies during] the Second Intifada. Courage to Refuse was part of this, and it generated a more critical form of journalistic coverage.”

In response, Levy says, the political leadership doubled down on the sense of emergency in Israeli society. “On March 2002, following the suicide attack in the Park Hotel in Netanya, Sharon drafted the reserve forces under emergency orders, and reconquered the Palestinian cities in the West Bank. Sharon knew that drafting reserve soldiers sent a message to the public. It rallied everybody to the flag. It was a key moment in the success of the political echelon to counter opposition to its actions during the Intifada — Courage to Refuse included.”

It was then, during the early months of 2002, as dozens of Courage to Refuse members were serving their prison terms (at one point that number reached as many as 50 refusers — soldiers and officers — in prison at the same time), when the government was able to take control over the narrative. The Israeli public came to view the Second Intifada as an existential battle: a response to a premeditated attack by both Fatah and Hamas. The destruction of Yasser Arafat’s Palestinian Authority was legitimized; the new PA which would later replace it would no longer be a quasi-independent entity or a state in the making, but a subcontractor within the infrastructure of the occupation.

‘The option to say no exists’

Courage to Refuse continued to operate for several years, but its impact was diminished. It did inspire other letters of refusal: from elite units, Air Force pilots, and veterans of the prestigious intelligence unit 8200. One year earlier, a letter from high schoolers who refused to serve in the military altogether over their opposition to Israel’s occupation resulted in several of them receiving months-long prison sentences; in the years that followed, dozens more Israeli teens would be put on trial and serve long prison terms — much longer than those handed down to members of Courage to Refuse — for their refusal to serve. There were more women as well as people from the Israeli periphery among them.

But despite the enormous sacrifice of the refusers, they failed to generate significant political influence, remaining largely symbolic and individual in their nature. The center of gravity on the left has moved to its more radical elements, while relatively small groups like Anarchists against the Wall and Ta’ayush, as well as human rights organizations, have reshaped the Jewish-Israeli left’s opposition to the occupation.

Since 2002, the Israeli military has undergone significant changes — so much so, says Levy, that “one cannot imagine something like ‘The Combatants’ Letter’ happening today.” A far larger proportion of combat soldiers are now recruited from the national-religious sector and the socioeconomic periphery, who see the army as a vehicle for social mobility. New units have been formed which specialize in carrying out the duties of controlling Palestinians under occupation, while reservists have been diverted, for the most part, away from serving in the West Bank and Gaza.

The Combatants’ Letter was part of a transformative moment in the history of the occupation and Israel’s relations with the Palestinians, and in the history of the Israeli left. For many people, myself included, refusing was also part of a personal transformation, a gateway drug for a whole new approach to viewing the conflict.

“It was a bridge to a new place,” agrees Zonshiene, who is the head of the board of the human rights organization B’Tselem (which lately began to label the entire Israeli regime as one of apartheid). “I also realize how long the road is from where I stood to the ways in which I understand the state of affairs today. Still, I think any refusal – certainly not just ours – is meaningful, especially if it is public, and even if it’s considered marginal.

“If someone would have told me [back then] that the army would bomb Gaza from aircraft, it would have seemed crazy to me,” he continues. “We refused to do far less. So if things get worse, and they certainly have the potential to get much worse, people need to be reminded that the option to say ‘no’ exists.”

Correction: The original version of this article stated that the attack on the Park Hotel in Netanya took place in March 2003. It has been amended to reflect the fact that it occurred in March 2002.

%20(2)%20(1)%20(1).jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.