A crisis of the post-war Sinhala nationalist state – few thoughts – Sunil Bastian

By Sri Lanka Brief-

Inability of the post-war centralised Sinhala nationalist state to satisfy demands of global finance capital has led to the biggest economic crisis of the post-colonial period. The reason for this cannot be reduced to one single factor but must be based on an analysis of the evolution of the post-war state in the current international context.

The role of China in the post-war Sri Lankan state

Let us take one example to illustrate this point – the role of China. Most economic analysis of the current crisis has focused on infrastructure investment supported by Chinese loans, and its impact on the economic crisis. But the recent improvement in relations between China and the Sri Lankan state, which led to this investment, began with Chinese support to the military efforts to consolidate the territory of the centralised Sinhala nationalist state. These developments took place in a context where the Chinese state has become stronger, due to its capitalist growth under global neoliberal capitalism. In a world characterised by global capitalism and competing states the Chinese state has its own strategic and foreign policy objectives. This is no different from the behaviour of other states. These factors are a part of the Chinese decision to help in the war effort, and subsequent expansion of Chinese capital in post-war infrastructure development. Therefore, the role of China in the post-war Sri Lankan state cannot be understood by confining ourselves to an economic analysis. It has to take into account of the post-war state formation process.

Leaving aside a much more comprehensive analysis of the current crisis to another occasion, the focus of this short article is on one dimension of the post-war state – the status or decay of the political institutions through which the political elite control the state. This is a main focus of protests that came up in Sinhala majority areas as a reaction to the economic collapse. It is clear that the political slogans of these protests reflect a lack of trust in the key political institutions that control the state which were established through the 1978 constitution.

To begin the discussion, it is relevant to remind ourselves how this political structure was established. This came about because of the political power enjoyed by the United National Party (UNP) after 1977 general election. The main political agenda of the UNP was to transform the economy into one that emphasised markets, the private sector, and openness to global capitalism. This was the start of a new period of capitalist transition in the post-colonial period. J.R. Jayewardene, who led the UNP in this election, understood the challenges that these economic reforms would face from the Sinhala majority long before 1977. His main concern was the political power reflected in the parliament which would be determined by the vote of the Sinhala majority. In 1966, in the keynote speech to the 22nd annual session of the Ceylon Association for the Advancement of Science, he argued for the need to establish a powerful directly elected president to carry out unpopular economic reforms. He wanted a powerful president who would not have to consider the ‘whims and fancies’ (his words) of the parliament. In the same speech, he proposed a proportional system of elections (Proportional representation-PR) to elect the parliament.

The UNP won the 1977 election securing 50.9 per cent of valid votes. This was the highest received by a winning party in a general election since independence. In a political space defined by ethnicity, Sinhala majority districts had 84.4 per cent of registered voters and elected 136 out of 168 MPs. The UNP won 129 of these. Because of the peculiarities of the first-past the -post system of elections (FPP), the UNP electoral base translated into 140 seats in a parliament of 168 or a five-sixths majority.

Using the parliamentary majority Jayewardene moved quickly to enact a new constitution and establish a presidential system. The election was in July 1977. On 22 September 1977 he ushed through a bill amending the 1972 constitution, which established a directly elected president. The bill was not even discussed by the government parliamentary group, and only approved at cabinet level. There were only six speeches in parliament when this major change in the political structure controlling the state took place. The Speaker certified the bill on 20 October 1977. Subsequently a parliamentary select committee controlled by the UNP drafted a new constitution. It held 16 meetings. It used a questionnaire to canvas opinion, instead of public consultation. There were only 281 responses. Sixteen organisations and a Buddhist priest gave evidence before the Committee. The report of the Select Committee was tabled in June 1978 and debated in August 1978, and the new constitution became a law in September 1978.[1]

There were a number of reasons why a PR system suited the UNP’s economic agenda. First, the significant majorities that ruling regimes started to enjoy under the FPP system of elections could always be used to reverse new economic policies if the UNP lost power. Second, despite the majorities under FPP there was always an element of instability for the ruling regime, because under this system MPs could cross over from the governing side to the opposition. The PR system could end this autonomy. However, plans for the PR system did not go according to what the UNP planned. The UNP proposed a cut-off point of 12 per cent valid votes in an electoral district for a party to be eligible to have MPs. MPs were to be elected through a list system, with the party hierarchy deciding the order in the list controlling who had a chance of being elected. There was to a ban on cross-overs. These elements had to be changed due to resistance from members of political parties including some from the UNP. The cut-off point was reduced to 5 per cent and a preference vote replaced the list. MPs could go to courts tp appeal against any decision by the party to discipline them.

This history shows that it was the power wielded by the political party in power that was key in establishing the institutions that began to control the state through the 1978 constitution. Often the importance of political power in defining how states are controlled through institutions gets masked by discussions that focus on legal aspects. In short, constitutions are a product of the balance of political power.[2]

Controlling presidency Sinhala political elite

These constitutional reforms created a powerful centre of power in the office of the presidency. Controlling presidency become the most important political objective for the Sinhala political elite. Although politicians criticised the presidency when out of power, they were reluctant to give up this power when they became the president. Opposition to the presidential system has been absorbed by the idea of a reformed presidency. The main political parties that depend on the support of the Sinhala majority have accepted this position.

The presidential system also strengthened the idea of a state controlled by a strong centre. For Sinhala nationalists, it became a means of tackling the challenge of Tamil separatism. For those who saw capitalist growth as the panacea for Sri Lanka’s problems, a strong presidency was a means of ensuring political stability. A powerful presidency existed in the post’77 period, where the possibility to challenge the power of the president through societal mechanisms were weak. In addition, factors such as patronage politics, which seeped into all spheres of social life, and a traditional attitude of looking towards powerful leaders for solutions, made this office even more powerful. As soon as this kind of powerful centre of power was created, these factors generated a political culture based on loyalty towards the centre and the person who became president. In return the president ensured that loyal supporters, including sections of the capitalist class, got special benefits. as well.

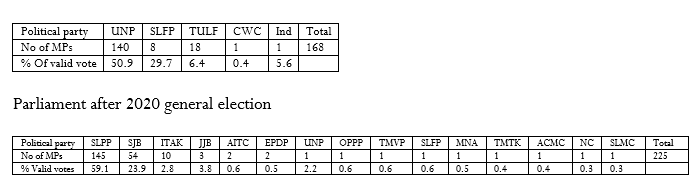

The other political outcome of institutions to promote the new period of capitalism is the emergence of a party system that is highly fractured. The political outcome of the success of consolidating the territory of Sinhala nationalist state also contributed to this. The tables below show the composition of parliament after the final election under the FPP system of elections and the last general election in 2020 under the PR system.

Parliament after 1977 general election

The parliament elected in 1977, the last election under FPP, consisted of two political formations – one led by the UNP and other by Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) that secured their support mainly from Sinhala majority areas; Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) representing the Tamil minority; and, for the first time in the post-colonial period, an elected member from the Indian Tamil community. There were four political parties in the parliament, and one independent member. In contrast to this, there are 15 political parties in the parliament elected in 2020. The two major parties that secured support from the Sinhala majority are divided. In addition, there is a new party that was a product of consolidation of the territory of the Sinhala nationalist state through military means – Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP).

PR system & coalition regimes

As a result of the political outcomes of the PR system of elections and divisions within the main parties, compared to what emerged under FPP towards the 1970s, coalition regimes have become more common. A combination of number of factors have led to a parliament where there are cross-overs, various deals with political factions to secure a majority in the parliament, division of state institutions and handing them over to members of coalition regimes, and the growth in the system of patronage politics. The ideological differences between major parties getting support from the Sinhala majority have disappeared. For many politicians, politics has become nothing more than securing a position of power to enjoy the benefits that follows. Often political power is used to secure benefits within a market economy.

With PR election petitions that could challenge the election of an MP under FPP disappeared. Under FPP you only had to look at what happened in a smaller spatial unit to prove that there had been election fraud and how it affected the result. Under PR the spatial units that MPs represented are much bigger and it becomes much more difficult to prove that electoral malpractice has an impact on results. This is almost impossible with a presidential election, where the entire country is the spatial unit for voting.

Global neo-liberal political project

In the period dominated by a global neo-liberal political project, a notion of governance, became the main concept through which questions of state reform have been analysed. This is totally inadequate for understanding politics and power within the state and their impact on policy-making process. Implicitly, it promotes liberal democratic state as some sort of a universal norm. Society is assumed to be a collection of individuals. State reform is reduced to enacting laws and establishing certain mechanisms. It is totally inadequate when it comes to understanding state formation in a multi-ethnic society. On the economic front, the political objective is reforming the state to promote capitalism.

It is time to take the debate on state reform beyond what is implied by the concept of governance. The crisis that the post-war Sri Lankan state is facing is multifaceted. Globally, it is clear that the neoliberal vision of the world, which projected global capitalism as a benevolent system that incorporates more and more people into a market economy, establishing liberal democracies and brings about an interconnected and peaceful world, is being questioned. There are signs that the combination of the impact of Covid and the war in Ukraine can precipitate a much bigger crisis in global capitalism. It is in this context that the post-war Sri Lankan state has once again gone to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a bail-out. Whatever the nature of the agreement with the IMF, it will be implemented in a society that still bear the scars of an armed conflict that went on for 30 years and the socio-economic impact of 40 years of more liberal economic policies. When it comes to the fate of the socially marginalised, we are hearing the usual idea of ‘protecting vulnerable’ that we heard 40 years ago. But who are these vulnerable in the current context, how do we identify them, who decides these criteria, how are they selected, how to protect these processes from patronage politics and finally can the socially marginalised be protected only by focusing on them? How about changes at the level of economic elite and relationship between this elite and socially marginalised? These are very specific question that can be used to push the debate on governance beyond its liberal framework.

[1] Empirical details are from Wilson A. 1980. The Gaullist System in Asia: The Constitution of Sri Lanka (1978). London: Macmillan Press

[2] See Linda Calley, 2021.The Gun, the Ship & the Pen: Warfare, Constitutions and Making of the Modern World. London: Profile for a history linking political powere and constitution making.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.