Raising Kachchativu issue was both needless and ill-timed

2 June 2022

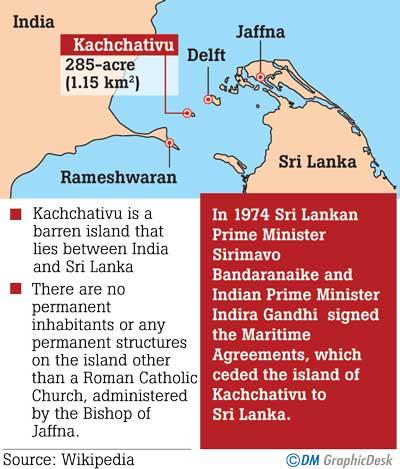

The Tamil Nadu Chief Minister rendered a disservice to India and its relations with Sri Lanka by raising the Kachchativu issue with the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi at a public function in Chennai on May 27. The demand for “retrieving” the Palk Strait Island to give Tamil Nadu fishermen fishing rights around Kachchativu, was both needless and ill-timed.

It reopened a settled issue, put a spoke in the wheel of Modi’s “Neighbourhood First” or Friendship with Neighbours policy, and added to the fears of North Sri Lankan Tamil fishermen already tormented by poachers from Tamil Nadu.

The timing of Stalin’s demand was inappropriate, coming at a time when Indo-Lankan relations were touching unprecedented heights thanks to New Delhi’s generous (US$ 3.5 billion) help to Sri Lanka at a time of dire need. The demand also followed Tamil Nadu’s gifting of humanitarian aid to Sri Lanka worth US$ 16 million, the value of which was in danger of being negated by the demand for Kachchativu.

Make it worse, the Indian media quoted the Tamil Nadu Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) chief, K. Annamalai, accusing Stalin’s party the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) and Indira Gandhi of “gifting” the island to Sri Lanka in 1974. The Tamil Nadu BJP’s intervention created apprehensions in Sri Lanka about the BJP-led government in New Delhi taking up the sensitive issue. Indian commentators even said that New Delhi should use its growing geopolitical clout to get Colombo to agree to a transfer of the island.

Make it worse, the Indian media quoted the Tamil Nadu Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) chief, K. Annamalai, accusing Stalin’s party the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) and Indira Gandhi of “gifting” the island to Sri Lanka in 1974. The Tamil Nadu BJP’s intervention created apprehensions in Sri Lanka about the BJP-led government in New Delhi taking up the sensitive issue. Indian commentators even said that New Delhi should use its growing geopolitical clout to get Colombo to agree to a transfer of the island.

On the Sri Lankan side, K.Rajachandran, President of the Ambal Fishermen’s Cooperative Society, Karainagar, Jaffna, feared that once the island went into India’s hands, Tamil Nadu fishermen could use it as a forward base to further extend their intrusions into Sri Lankan waters. He also feared that Colombo would turn a blind eye to this as the affected fishermen would not be the majority Sinhalese but minority Tamils. Rajachandran also pointed out that Tami Nadu fishermen have been coming up to Sri Lankan shores well past Kachchativu routinely anyway. Therefore, securing it would be of no great value for them.

New Delhi against retrieval

However, it is certain that New Delhi will not revise its consistent stand that there is no case for retrieving the island. When Tamil Nadu Chief Minister J. Jayalalithaa took the issue to the Supreme Court, the Indian government challenged her contention that Kachchativu was Indian Territory that was gifted away to Sri Lanka. New Delhi insisted that Kachchativu was always a “disputed” territory and that the dispute had been settled through negotiations.

The Central government told the Supreme Court: “Both countries examined the entire question from all angles and took into account historical evidence and legal aspects. This position was reiterated in the 1976 agreement. No territory belonging to India was ceded nor sovereignty relinquished since the area in question was in dispute and had never been demarcated.” The contention of Jayalalithaa that Kachchativu was ceded to Sri Lanka “was not correct and contrary to official records,” the Centre said.

According to an informed source, Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee had also written to Jayalalithaa saying that Kachchativu was a settled matter and requesting her not to raise it. Sources said that the current BJP government will also not be willing to ruffle Colombo’s feathers.

Difference in Interpretation

One of the points of conflict has been the difference in the interpretation of the 1974 and 1976 Indo-Lankan Agreements. While the Tamil Nadu government and Tamil Nadu fishermen contend that the agreements allow fishermen of the two countries to exercise their “traditional rights” which includes fishing rights around Kachchativu, the Indian and Sri Lankan governments point out that fishing rights were not given. What was given was only the right of the Indian fishermen to dry their nets in Kachchativu, to attend the annual St. Anthony’s Feast without a visa and the right of navigation, not fishing.

The Indian government had in fact told the Supreme Court that the term traditional rights “is not to be understood to cover fishing rights around the island to Indian fishermen.”

But the Tami Nadu government has argued that the ban on fishing was not part of the agreement but was there only in the letters exchanged between two signatories to the agreement, and therefore not binding.

1974 Agreement

Article 4 of the 1974 Agreement stipulates that each State shall have sovereignty and exclusive jurisdiction and control over the waters, the Islands, the Continental Shelf and the sub soil on its side of the Maritime boundary in the Palk Strait and Palk Bay. Kachchativu Island was determined as falling within Sri Lankan waters.

Article 5 provides that “Subject to the foregoing, Indian fishermen and pilgrims will enjoy access to visit Kachchativu, as hitherto, and will not be required by Sri Lanka to obtain travel documents or visas for these purposes.”

Article 6 states that “The vessels of India and Sri Lanka will enjoy in each other’s waters such rights as they have traditionally enjoyed therein.” The expression “traditional rights” is interpreted in Tamil Nadu as including “fishing rights” also.

1976 Agreement

Art 6 of the 1976 agreement says: (1) Each Party shall have sovereignty over the historic waters and territorial sea, as well as over the islands, falling on its side of the aforesaid boundary. (2) Each Party shall have sovereign rights and exclusive jurisdiction over the continental shelf and the Exclusive Economic Zone as well as their resources, whether living or non- living, falling on its side of the aforesaid boundary. (3) Each Party shall respect rights of navigation through its territorial sea and exclusive economic zone in accordance with its laws and regulations and the rules of international law.

The Sri Lanka view is that, by this Article, only navigational rights of the vessels of both Sri Lanka and India over each other’s waters have been preserved and not fishing rights.

The Sri Lankan Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated: “The preparatory notes leading to the finalization of the rights of the two Parties, clearly manifests that the rights of pilgrims under Article 5 were restricted to attending the annual feast of the church and the rights of access of fishermen were restricted to drying their nets and catch. Therefore, the provisions in Article 5 and 6, taken together, do not confer any fishing rights on the Indian fishermen or vessels to engage in fishing in Sri Lankan waters. The 1974 and 1976 Agreements, taken together with the Exchange of Letters, that was signed between Kewal Singh, the then Foreign Secretary to the Government of India, and W.T. Jayasinghe, then Secretary to the Ministry of Defence and Foreign Affairs of Sri Lanka, has put the question of fishing rights beyond doubt.”

Exchanged Letters

The Lankan Ministry further said: “Paragraph 1 of the Exchange of Letters very clearly rules out any fishing rights for the fishermen of the two States in the waters of the other State which reads as follows: Fishing vessels and fishermen of India shall not engage in fishing in the historic waters, the territorial sea and the EEZ of Sri Lanka nor shall the fishing vessels and fishermen of Sri Lanka engage in fishing in the historic waters, the territorial sea and the EEZ of India, without the express permission of Sri Lanka or India, as the case may be.”

“Therefore, with the signing of the 1976 Agreement and the Exchange of Letters, the maritime boundary between Sri Lanka and India stands settled, and the Letters of Exchange clearly prohibits fishing vessels and fishermen of one country fishing in the others’ waters,” the Sri Lankan Foreign Ministry concluded.

%20(1)%20(1).png)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.